The move from a generic feed-in tariff (FiT) regime to project-specific competitive bidding for tariff determination has disrupted the entire wind power segment. Its ripple effects can be felt in every aspect of project development, including cost economics and project financing. As a result, financial parameters have undergone a significant shift, in tune with the evolving risk profile and changing profit margins of projects.

While traditional capital and financial costs continue to be the primary factors that determine optimum cost economics, offtaker credit ratings, project implementing agencies and the strength of power purchase agreements (PPAs) are playing an increasing role in this. Since these parameters are highly project and tender specific, providing generic costs and tariffs for wind power projects has become obsolete. As such, the Central Electricity Regulatory Commission (CERC) chose not to release benchmark tariffs for wind power projects for 2017-18 and 2018-19. Such developments have not only altered the financial landscape for projects, but also impacted the cost economics and sources of funds considerably.

The Solar Energy Corporation of India (SECI) has auctioned 6 GW of wind power capacity through central tenders over the past year. Tariffs fell from around Rs 5 per kWh in the FiT era to Rs 3.46 per kWh in the first auction. Successive auctions saw a decline in tariffs, reaching at Rs 2.43 per kWh, which was discovered in the 500 MW Gujarat auction in December 2017. The tariffs then rose to Rs 2.85 per kWh in March 2018, with a 500 MW auction by Maharashtra. However, they seem to have stabilised at Rs 2.50 per unit, discovered in the latest auction for 2,000 MW by SECI in April 2018.

Given that the states are now increasingly moving towards competitive bidding for wind power projects, the respective state electricity regulatory commissions (SERCs) have not published benchmark FiTs for 2018-19. However, in an interesting deviation from the ongoing trend, the Tamil Nadu Electricity Regulatory Commission (TNERC) released generic tariffs for the wind power segment for 2018-19.

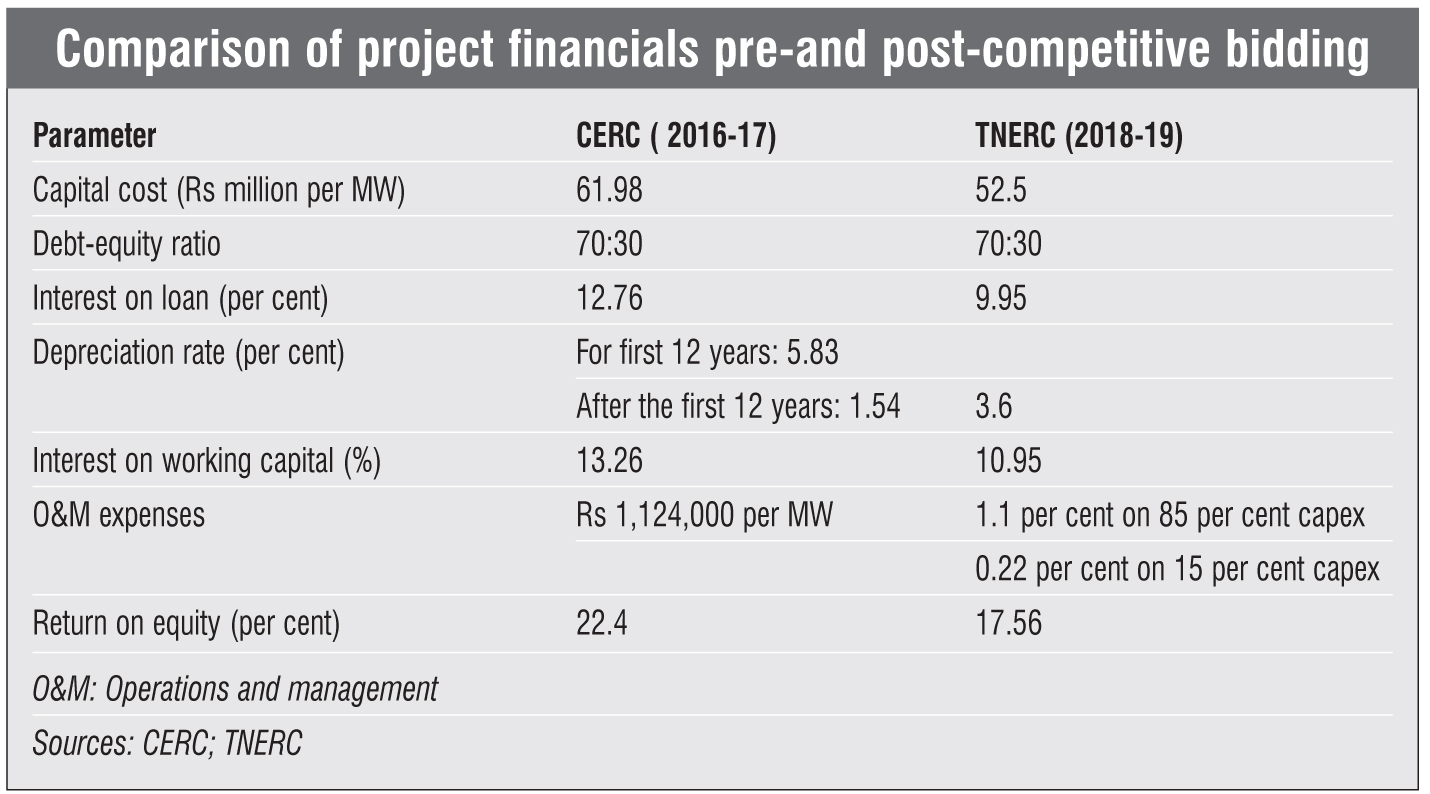

A comparative analysis of the CERC benchmark tariffs in 2016-17 and TNERC’s generic tariffs for 2018-19 reveals the evolution of cost parameters for the segment. The capital cost of wind turbines considered by TNERC in its 2018-19 tariff order is 15.3 per cent less than that the CERC in 2016-17. Meanwhile, the breakdown of capital costs as given by the CERC has been retained by TNERC even in the post-competitive bidding era – machinery costs are 85 per cent, civil works are 10 per cent, and land costs are 5 per cent. With the significant fall in tariffs, the risk profile of wind power projects has improved considerably. This has helped reduce the interest on loans provided by banks and other multilateral institutions for the development of wind power projects.

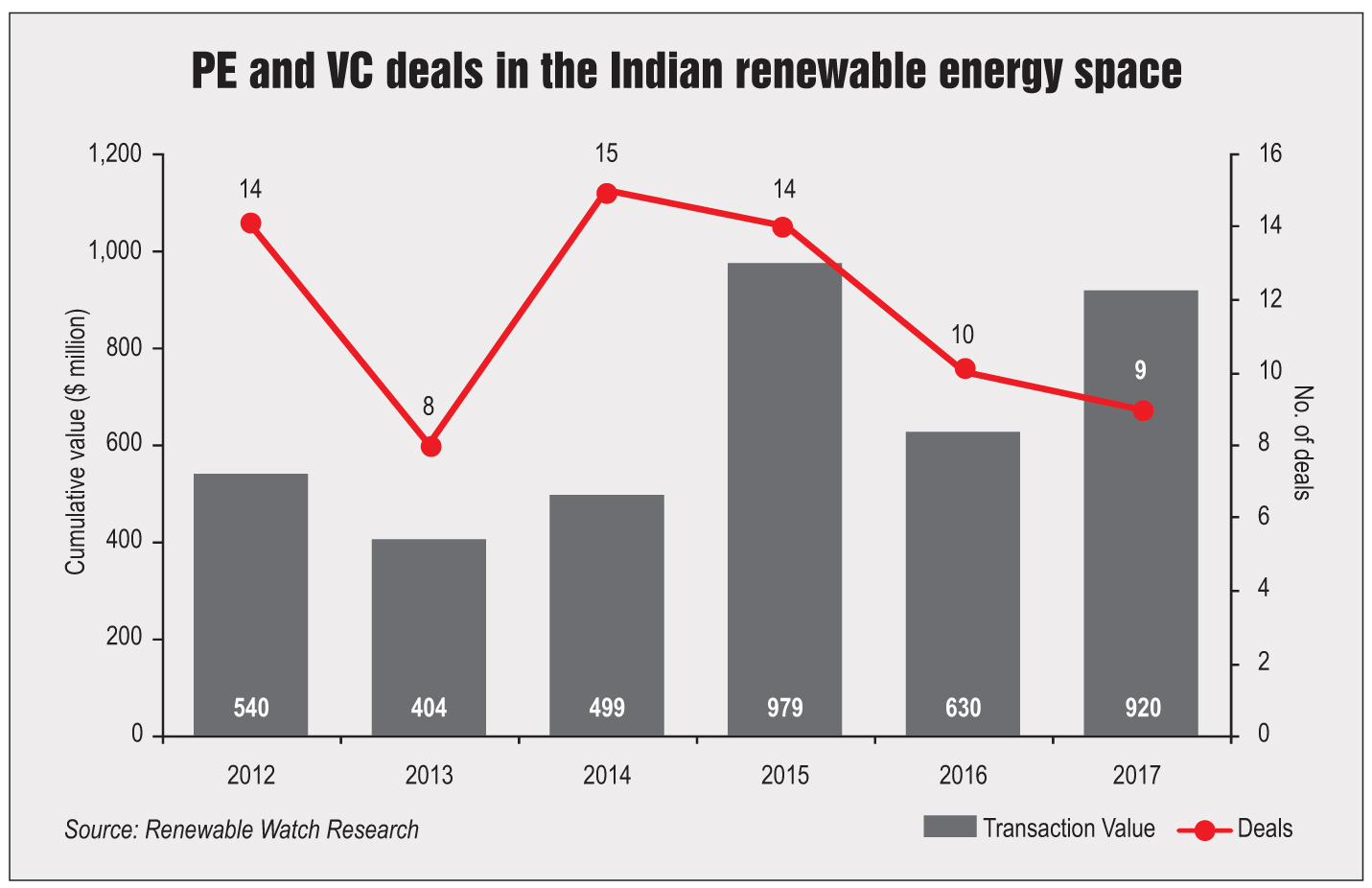

This is one of the favoured modes of project financing, especially in the wind power segment. With competitive bidding in place, inhibiting factors such as technology risks, low growth and subsidy dependence have now been eliminated, opening up the market to private equity (PE) players. According to reports, PE capital investment in the Indian renewable energy sector increased by 47 per cent, from $630 million in 2016 to $920 million (through nine deals) in 2017.

Given that the renewable energy sector has emerged as a significant opportunity for investment over the past decade, most companies in the space have functioned as start-ups until recently, funded by domestic and international venture capital (VC). It has, therefore, emerged as a promising way of raising funds by companies trying to enter the wind power segment.

However, with competitive bidding, few start-ups will be able to compete in the low-tariff environment. With high entry barriers, the VC and PE modes of financing are expected to see fewer, but larger, deals over the next few years. Moreover, once the market stabilises and capital costs fall in tandem with low tariffs, the profit margins will increase, leading to a new wave of companies competing for capacity that would require a fresh infusion of capital. Another trend emerging in the Indian renewable energy market is that of companies going public and diluting their equity stake. In the wind energy segment, companies are increasingly considering launching initial public offerings (IPOs) to raise capital for project development. Mytrah Energy, ReNew Power and Adani Green Energy have all recently announced plans to take the IPO route.

The debt component of the wind power segment is usually financed by instruments such as loans, convertible debentures and notes. However, loans provided by domestic banks for wind power projects have typically had higher interest rates due to the high tariffs and consequent high offtake risk. With a steep fall in tariffs, the interest rates are expected to decrease while the tenor of loans is likely to increase, thereby reducing the cost of capital.

Meanwhile, international banks and multilateral financial institutions have started providing low-interest loans to wind power projects. The fall in tariffs and the trajectory for defined capacity have improved the risk portfolio of wind projects. The tenor of loans given by these institutions is typically around 15-18 years as compared to 6-10 years by domestic banks.

The structure of financing for wind power projects is evolving with newer mechanisms gaining traction in the segment. Due to lower margins, the emerging instruments will need to have a long-term outlook with high capital raising capability. Of these, green bonds have emerged as a popular option for debt financing in the renewable energy sector, as these offer lower rates than other security and debt financing instruments. There have been three bond issuances in India in the second half of 2017-18, totalling a value of $1.2 billion. In the first seven months of 2017, India’s green bond issuance had reached $2.1 billion, bringing the total value for 2017-18 to over $3.3 billion.

Another emerging mechanism is the credit guarantee scheme, which involves a third-party credit guarantee agency assuming post-construction project performance risk. This insulates the lender from payment delays and defaults, thereby guaranteeing its return on investment. The ailing health of discoms has resulted in reduced investor interest in the segment, which makes this option helpful in the Indian context. It enables financial institutions to extend loans or invest in bonds at competitive prices. SECI’s first tranche of wind tenders for 1 GW, floated in February 2017, is an example of a credit guarantee scheme, its key feature being that each winner would sign a guaranteed PPA with PTC India Limited, which, in turn, would sign PPAs with the discoms.

India is expected to install 25.5 GW of wind power capacity over the next four years to achieve the 60 GW target. Renewable Watch Research has analysed the likely annual capacity addition and investment requirements for the four-year period. Assuming a gestation period of about 18 months, the capacity addition in 2018-19 is likely to be low, given that only 1.5 GW was auctioned in 2016-17. In 2017-18, another 4 GW was tendered, which is likely to see execution by 2018-19. According to the trajectory released by the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE), 10 GW of capacity is expected to be tendered in both 2018-2019 and 2019-20, which will then be commissioned by 2022.

The cumulative investment required in the wind power segment over the next four years is likely to be Rs 1.2 trillion. The investment requirement considers the capital costs for 2018-19 at Rs 52.5 million per MW (as given by TNERC in its order for benchmark tariff of wind power). A nominal reduction in capital costs of 4 per cent in 2019-20 and 3 per cent in 2020-21 as well as 2021-22 has been considered.

Given the huge amount of funding required, the financing parameters will need to be increasingly competitive in order to reduce costs while maintaining the desired capacity addition trajectory.