With a target of 100 GW of installed solar power capacity by 2022, the government is counting on all segments to achieve its ambitious plans. Of the total 100 GW, 40 GW has been earmarked to be sourced from rooftop solar. Pegging the country’s rooftop solar potential at 124 GW, the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy recently increased the sanction from Rs 6 billion to Rs 50 billion for the implementation of grid-connected rooftop and small solar power plant systems under the National Solar Mission up to 2019-20.

Rooftop solar systems generate power that is either entirely fed into the grid or is utilised for captive consumption and the excess power is fed into the grid. Moreover, when the power generated is insufficient, the user can draw power from the grid.

Rooftop solar systems allow for the utilisation of vacant and unutilised roof spaces. Low gestation periods, coupled with lower transmission and distribution losses, make it a viable venture for a wide gamut of investors, some of whom had hitherto been unable to enter the lucrative renewable energy space. Since the daytime rooftop generation may not be consumed entirely, and the industrial or commercial organisation may require more power at night, the discoms’ distribution network can be used as a source of storage under net metering, partly solving the long-standing and complicated issue of energy storage. Moreover, rooftop solar projects help meet the renewable purchase obligations (RPOs) of eligible entities. Technical losses are minimised in such projects since power consumption and generation are intertwined and there is minimum transmission of power.

Net metering versus gross metering

Net metering is a process under which any solar energy generator can feed power in excess of captive consumption into the grid and get compensated by the discom for the same. This method acts as a driver of rooftop solar adoption by high-paying consumers. Such consumers are already paying a high price for conventional energy and can be motivated to switch to solar through net-metering agreements. Further, net metering reduces the risk of delayed payments by discoms. Of the total 36 states and union territories, 30 have net-metering policies in place, though the implementation of these remains sketchy. Some of the states with a good net metering implementation status are Gujarat, Punjab, Telangana, Delhi, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh.

Gross metering systems are aimed at roof owners/third-party investors, who would like to sell power to the discoms by using roofs owned by them or another party for solar power generation. Gross metering does not allow for captive consumption and all the energy generated is fed into the grid at a predetermined feed-in-tariff (FiT). This technique also protects utilities from the loss of cross-subsidising consumers and fixed cost recovery. In addition, the power generated under gross metering can be used by enterprises to fulfil the RPOs of eligible entities.

The most important caveat of net metering is that it is viable only for high-paying consumers. Regulations by state utilities often lead to underutilisation of roofs. Under gross metering, FiT is usually higher than the average power purchase cost, leading to a short-term cash flow burden on the utility’s balance sheet. Further, higher procurement cost translates into higher tariff for consumers. Implementation of net metering continues to remain poor in many states.

Capex model

The capex model is the most common business model for rooftop solar deployment in the country. Under this model, the roof owner is the owner of the rooftop solar system and bears the entire capital expenditure of the project. The gains from tariff savings also accrue to the roof owner.

The capex model has been losing ground in the recent past since it is unviable for residential consumers and small entities, which are, in most cases, cash-strapped and cannot meet the huge upfront costs associated with it. Further, these entities are unable to secure bank funding.

Opex models

RESCO

The renewable energy service company (RESCO) model is an alternative to the capex model. Under this, the developer bears the capital expenditure of the project. The developer also oversees the installation and operation of the rooftop solar system and undertakes its maintenance. The developer and the roof owner enter into an agreement by way of which roof owner may either consume the electricity generated or received appropriate monthly rent from the developer for the duration of the project in exchange for allowing the developer access to his rooftop.

SPAAS

The process of installing panels and solar projects can be complex and expensive. Technical knowledge required to install rooftop solar projects, size of the premises and cost of standard solar photovoltaic (PV) panels lead many enterprises to believe that installing solar panels to adequately power their buildings is unaffordable. Solar-power-as-a-service (SPAAS) is a business model that changes the way commercial and industrial solar consumers pay for solar power. SPAAS is a kind of a solar subscription service with monthly payment plans, which makes solar power more viable for companies and enterprises.

The developer and the consumer enter into a power purchase agreement (PPA) at a predetermined non-negotiable rate, insulating them from any future increase in industry costs, which cannot translate into higher prices. The consumer is free of the technical risks associated with the solar plant. At the end of the PPA term, the solar plant is transferred to the consumer.

Based on the consumption choice and requirement, the opex model branches out into two types – rooftop leasing and PPA. From the perspective of consumers, the highest uptake of opex models has been in government projects, followed by industrial and commercial ones.

- Rooftop leasing (under gross metering) – In leasing under gross metering, the developer leases the rooftop and pays a fixed lease or rent to the roof-owner for the duration of the lease period. The developer finances, operates and maintains the rooftop solar system. The solar energy generated is fed into the grid at a predetermined FiT approved by the regulator.

- PPA (under net metering) – Under this model as well the developer finances, operates and maintains the rooftop solar system. The energy generated, however, is not fed into the grid directly but is sold to the building owner. The roof owner can sell any excess power, over and above his personal consumption, to the utility through the net metering system.

Trends and market share

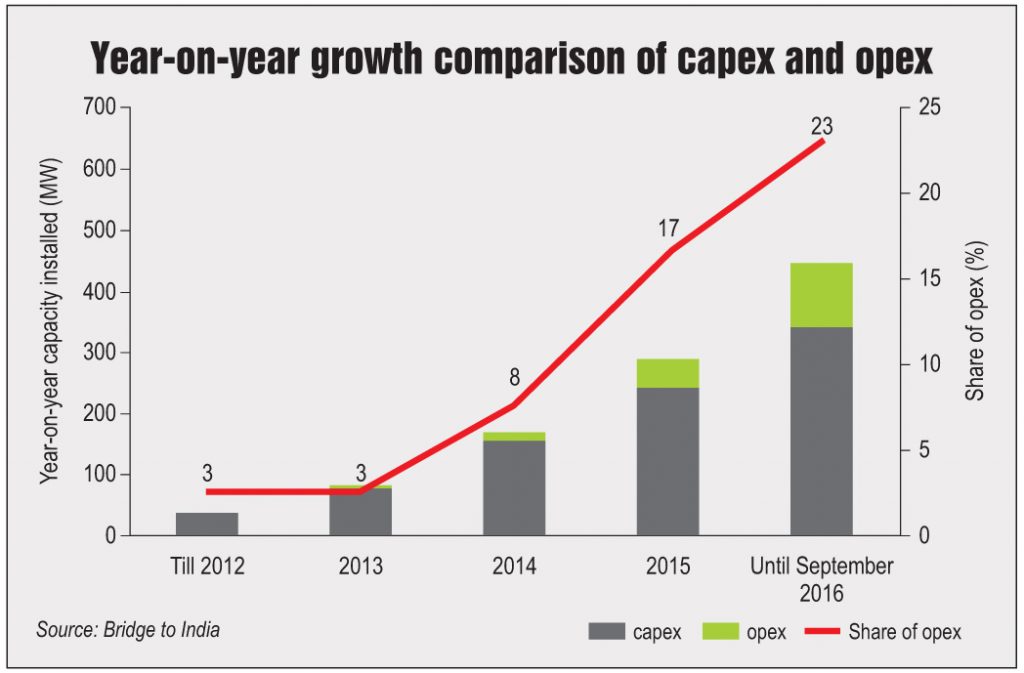

The capex model has been the most prevalent model in the recent and accounts for close to 83 per cent of all rooftop projects. However, in the past few years, the opex model has been gaining ground due to a number of reasons. Its year-on-year share increased from barely 3 per cent in 2012 to 23 per cent in 2016. Further, in the first three quarters of 2016, the opex market grew by a remarkable 114 per cent compared to a 42 per cent growth in 2015.

This model, however, requires a large initial investment that often acts as a deterrent. The rollback of government subsidies and the removal of accelerated depreciation benefits have increased the cost of installation through the capex model. In addition, efficient operations and maintenance of solar projects, being technical in nature, is difficult to carry out by roof owners, who in most cases lack the technical know-how required for the same.

According to consulting firm BRIDGE TO INDIA, the installed rooftop solar capacity stood at 1,396 MW as of March 2017. There was an increase of 678 MW during 2016-17 and another 1,232 MW of capacity is expected to be added in 2017-18. Of the total installed capacity, 42 per cent can be attributed to the industrial sector, 22 per cent to the residential sector, 22 per cent to the commercial sector and almost 14 per cent to the government sector.

Although the segment has grown, only a few players have been able to scale up operations. As of March 2017, only Tata Power Solar had an installed capacity of over 100 MW. The steady uptake of rooftop solar has led to the entry of new players, which has intensified competition in the segment.

According to Mercom Capital, the top five companies – Tata Power Solar, CleanMax Solar, Vikram Solar, Harsha Abakus Solar and RelyOn Solar – accounted for 39 per cent of the rooftop market and the top 20 companies accounted for almost 80 per cent of all rooftop installations. Among government entities and utilities, Indian Railways, the Airports Authority of India and various port trusts are helping drive rooftop solar growth.

As of February 2017, Tata Power Solar had commissioned 124 MW of rooftop projects and 20 MW is under development. Azure Power had commissioned 21.9 MW of rooftop solar projects as of March 2017, and 83.9 MW of projects are in the pipeline, taking its total portfolio in the country to over 100 MW. Rays Power Experts has commissioned an estimated 24 MW of rooftop solar and has another 10 MW of rooftop solar projects at various stages of development, as of March 2017.

Moving forward

So far, 1.02 GW of rooftop solar capacity has been installed against the targeted 5 GW for 2017-18. According to BRIDGE TO INDIA, approximately 11.9 GW of new rooftop solar capacity is expected to come up between 2017 and 2021. Although significant, this figure is only a small fraction of the substantial 40 GW being targeted by the government.

Going forward, rooftop solar capacity addition is expected to gain momentum. Rapidly falling costs have improved the growth prospects. Moreover, the government is making efforts to boost demand by public sector units (PSUs), as is evident from the large size of sanctions and installations by PSUs and several government departments.