The idea of long-range grid connectivity is gaining traction in many parts of the world. Southeast Asian (SEA) countries have formed the Association of Southeast Asia Nations (ASEAN) to promote power trade and have set up the ASEAN Power Grid (APG) programme. In South Asia (SA), Bangladesh, Bhutan, India and Nepal (BBIN) are exchanging power through bilateral channels in power markets, and soon further through trilateral transactions via India. At the recent G20 conference held in India, regional cooperation was discussed, and the “One Sun, One World, One Grid” initiative was endorsed by all. Why do we need interregional connectivity? Building national grids is essential to meet domestic electricity demand, but connecting grids across countries and regions is essential to deliver low-cost renewable energy. Cross-border power trade can optimise generation costs and capacity, reduce fossil

fuel consumption, air pollution and carbon dioxide emissions, and increase renewable energy share. This cannot be fully tapped by one country alone, as each country experiences excess and deficits during the day because the demand always fluctuates wildly in all grids. Moreover, cost, investment and local air pollution can be reduced while increasing energy security and facilitating affordable energy access for development and economic growth. For growing economies such as Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Myanmar, the immediate availability of power through the setting up of transmission lines may be preferable, and they can gradually set up their own power generation so that their economies start to expand earlier. The availability of cheaper renewables-based electricity and the urgent need for decarbonisation are driving the need for more interconnections at the subregional, intra-regional and inter-regional levels. This could reduce the need for storage as renewable energy such as solar, wind and hydro power can be transmitted from neighbourhoods and even from a distance, if available and possible.

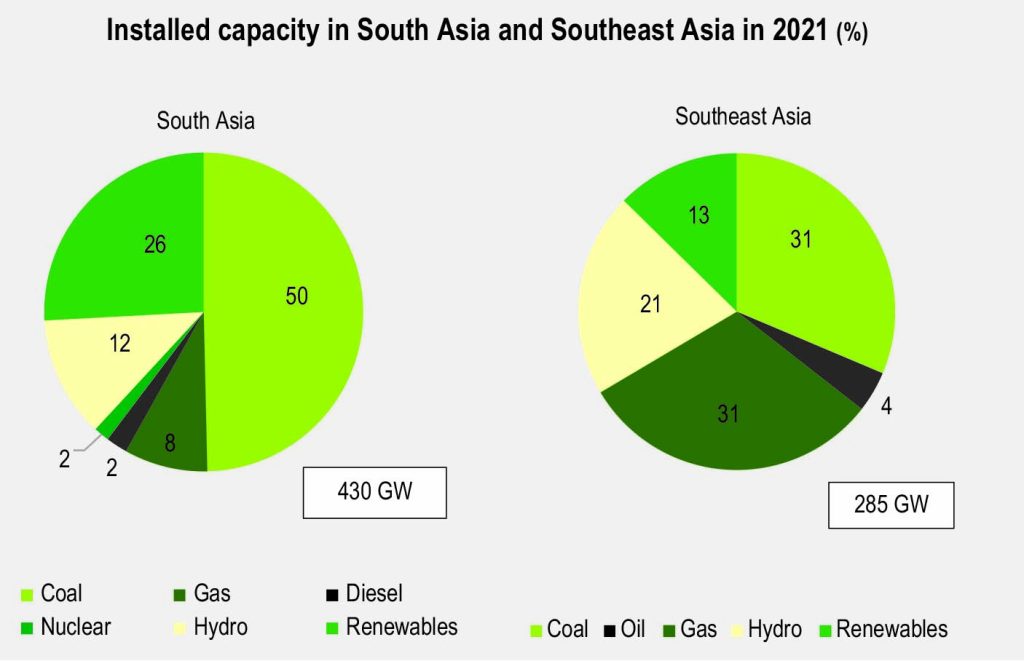

Installed capacity in the SA and SEA regions

In the SA region, approximately 60 per cent of the total 430 GW installed capacity was based on fossil fuels in 2021. Of this, coal accounted for 50 per cent, natural gas for 8 per cent and 40 per cent was based on non-fossil fuels.

In the SEA region, out of a total power generation capacity of 285 GW, approximately 67 per cent was based on fossil fuels, with 32 per cent from coal, 31 per cent from natural gas and 4 per cent from oil. Renewables accounted for 33 per cent, with approximately 20 per cent from hydropower. Among the countries in the region, Cambodia and Laos are the only countries where the share of renewables is significant.

Current electricity trade within the SA and SEA regions

South Asia

According to data from the Ministry of Power (MoP), in 2020, India exported 2,280 GWh of power to Nepal, 7,102 GWh (1,160 MW) to Bangladesh and 7 GWh (3 MW) to Myanmar, and imported 6,351 GWh from Bhutan. During winters, Bhutan imports power from India. Between 2000 and 2019, imports by Bhutan increased from 19 GWh to 96 GWh. There are interconnections between India and Bhutan at the 400 KV, 220 KV and 132 KV levels. Major 400 kV interconnections are from Tala in Bhutan to Siliguri in India. Nepal has fewer interconnections at present, but it is rapidly evolving and planning to build 10,000 MW of hydropower, with a significant portion intended for export. This electricity exchange is set to increase further.

To develop bilateral and trilateral trade between Bhutan or Nepal and Bangladesh, all interconnections have to be through India, and the involved parties have reached an agreement on this. The cumulative power transfer capacity through cross-border interconnections with neighbouring countries is about 4,230 MW, and this is expected to be enhanced to 6,360 MW, as outlined in Table 1.

In addition to government-to-government agreements, these countries are trading through power exchanges also.

Southeast Asia

Under the APG programme, the interconnections are grouped into three sub systems: the upper west system, located in the Greater Mekong subregion; the lower west system, located in Thailand, Indonesia (Sumatra and Batam), Malaysia (Peninsular) and Singapore; and the east system, which includes Brunei, Malaysia (Sabah and Sarawak), Indonesia (West Kalimantan) and the Philippines.

Presently, the upper western part of the SEA region is well integrated. Thailand is the largest electricity importer in the SEA region and has developed interconnections with almost all of its neighbouring countries (except Myanmar) through 20 transmission links, of which 17 are with Laos alone. Electricity import in Thailand has tripled from 10.7 TWh in 2011 to 33.4 TWh in 2021. Cambodia is the second largest importer and has imported a total of 3,830 GWh from Laos (1,763 GWh), Vietnam (1,247 GWh) and Thailand (810 GWh) in 2020.

Laos is the largest electricity exporter in the SEA region and is known as the battery of the region because of its large hydropower potential. Presently, the country exports electricity to Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam. Moreover, it has also started the supply of around 100 MW of electricity to Singapore under the Laos-Thailand-Malaysia-Singapore Power Integration Project from 2022. Cross-border power trade in eastern Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines is relatively small due to the barrier posed by the ocean. Therefore, interconnections with those islands have not yet been established.

Drivers for power trade

The need for a greater integration of renewables is well understood around the globe. Investment in the deployment of renewables is increasing and costs are continuously falling. However, awareness of grid connectivity as a tool to enhance renewable energy resources is only beginning to gain traction. Several long-term drivers determine the magnitude and direction of the flow of such trade:

Driver 1: Growth of electricity demand

As both the SA and SEA regions are in their economic and electricity growth phases, demand stagnation may not be a constraint for several decades. Their per capita electricity consumption has increased at almost a similar electricity consumption pace. However, the per capita in these regions is far below the world average of 3,200 kWh per capita. Therefore, electricity demand is likely to increase in order to catch up with the world average. The electricity demand is likely to increase to 5,375 TWh and 5,465 TWh in the SA and SEA regions respectively.

Driver 2: Energy resource potential

Both regions must transit to renewable energy for their security, cost-saving benefits, local environment preservation and to combat climate change. Due to high demand, they will need renewable energy resources and fossil fuels to support the grid for some time. In the SA region, India dominates with coal, accounting for 90 billion tonnes. Though Bangladesh has some natural gas reserves, it barely meets its own domestic needs for an extended period. SEA countries also have significant reserves of coal, oil and natural gas. In recent years, coal dependence has increased in the region, mainly for power generation, due to the availability of coal reserves.

The SA and SEA countries are blessed with renewable resources but are presently not meeting their own domestic electricity requirements due to the underutilisation of available domestic resources, along with financial and technical constraints. Despite the falling costs of renewable energy technologies, the contribution of solar PV and wind remains small, though some markets are now putting in place frameworks to better support their deployment. Both regions have favourable circumstances to trade because of large untapped resource availability (as shown in Table 2).

Driver 3: Time difference

The time difference between regions can be useful in exchanging surplus energy from solar, wind or hydro power for the optimal utilisation of energy. Even without the time difference, power trade is occurring in close proximity, such as between Nepal and India or Laos and Thailand. Moreover, due to variations in demand patterns, influenced by seasons, festivals, holidays (weekends) and the nature of activities (industrial, agriculture, etc.), trade can happen year round. Myanmar is 30 minutes ahead of countries such as Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Thailand, Vietnam, Brunei, Malaysia, Philippines and Singapore.

Driver 4: Seasonal variations

Currently, in Nepal and Bhutan, most hydropower plants are run-of-the-river type. During monsoons, due to high water flows, both countries generate surplus electricity and have low electricity demand. This surplus power can be exported to India and Bangladesh. In contrast, during lean months in the winter from November to March, when they face power shortages due to high electricity demand and low power generation, they import power from India. Seasonal variations are not that high in the SEA countries. Therefore, factors such as daily load curve, electricity cost and resource availability are key elements influencing power trade.

Both regions have shown willingness to decarbonise their respective power sectors. In South Asia, India has agreed to become net zero by 2070. Moreover, all countries are signatories to the Paris Agreement and have committed to achieving the climate goals and addressing issues of air pollution, which is high in all countries.

A long-term strategy for interregional connectivity

The SA and SEA regions are already familiar with and working on cross-border power cooperation within various regional groupings. Institutional recognition facilitates expedited decision-making processes and leads to systematic planning. Although BBIN trade started as late as 2013, it quickly reached 24 TWh within a span of nine years, despite the absence of a formal agreement or institution. This could be attributed to India’s state-of-the-art power exchange, which gives clearing prices every 15 minutes in a transparent manner. Additionally, there are dispute resolution mechanisms for national traders and discoms, which have fostered trust and facilitated the development of new power plants and transmission lines.

In the SEA region, the Heads of ASEAN Power Utilities/Authorities was set up in 1997. Since then, power trade has reached 36 TWh in 2020 and has increased connectivity substantially through the establishment of 27 transmission lines, facilitated by early agreements between participating countries. However, power exchange still does not exist. Renewable sources are dispersed with low energy density, and therefore the integration of sources over large space is needed. Hydropower or fossil fuels, and even nuclear, can provide substantial amounts of energy to generate electricity in one place. Such large-scale generation capacities are possible and remain necessary to meet the growing demand for electricity. We need more flexibility in transmission systems to achieve higher shares of renewable energy, which large areas in 17 countries and five time zones can provide.

Currently, the connection capacity of Myanmar with India is only 3 MW. If Myanmar accelerates its own development and participates fully, while developing its own hydropower and gas resources, it can create an ideal situation. The India-Myanmar-Thailand link does not yet exist but such a link can serve as a conduit for transmitting power among the two regions. In the SEA region, Thailand is the largest importer, with the maximum number of interconnections at 19, and Laos is the largest exporter of electricity in the SEA region, particularly to Thailand. Thailand needs to have more options for imports to enhance its energy security and economic sustainability. Under such a scenario, it needs to prepare to play an important role as a hub of interconnections.

Conclusion

Technically, interregional connectivity is not difficult, but politically, it is very challenging. In the meantime, each region needs to strengthen intercountry and intra-region trade, as well as increase generation and set up transmission and distribution links with countries so that power can go to every part of the respective countries. Moreover, as the share of renewables increases, the unexpected mismatch between load requirements and supply characteristics will increase, which can be costly and detrimental to progress and further transformation. Early planning of transmission links to all possible consumers can help mitigate these challenges. The more interconnected regions and countries become, the greater the likelihood that power can reach everywhere and benefit all citizens, not just those in the border linkage areas. Adequate emphasis on strengthening the distribution systems within each country, coupled with corresponding investments, is necessary to ensure that no areas within countries are isolated and short of power. This will also ensure 100 per cent electricity access to all consumers, much higher shares of renewable energy and faster decarbonisation at lower costs. As a result, exporting countries can embark on a new economic growth path, and importing countries can gain access to electricity earlier and at a lower cost. Moreover, peaceful relations can prevail with mutual interdependence.