By Khushboo Goyal

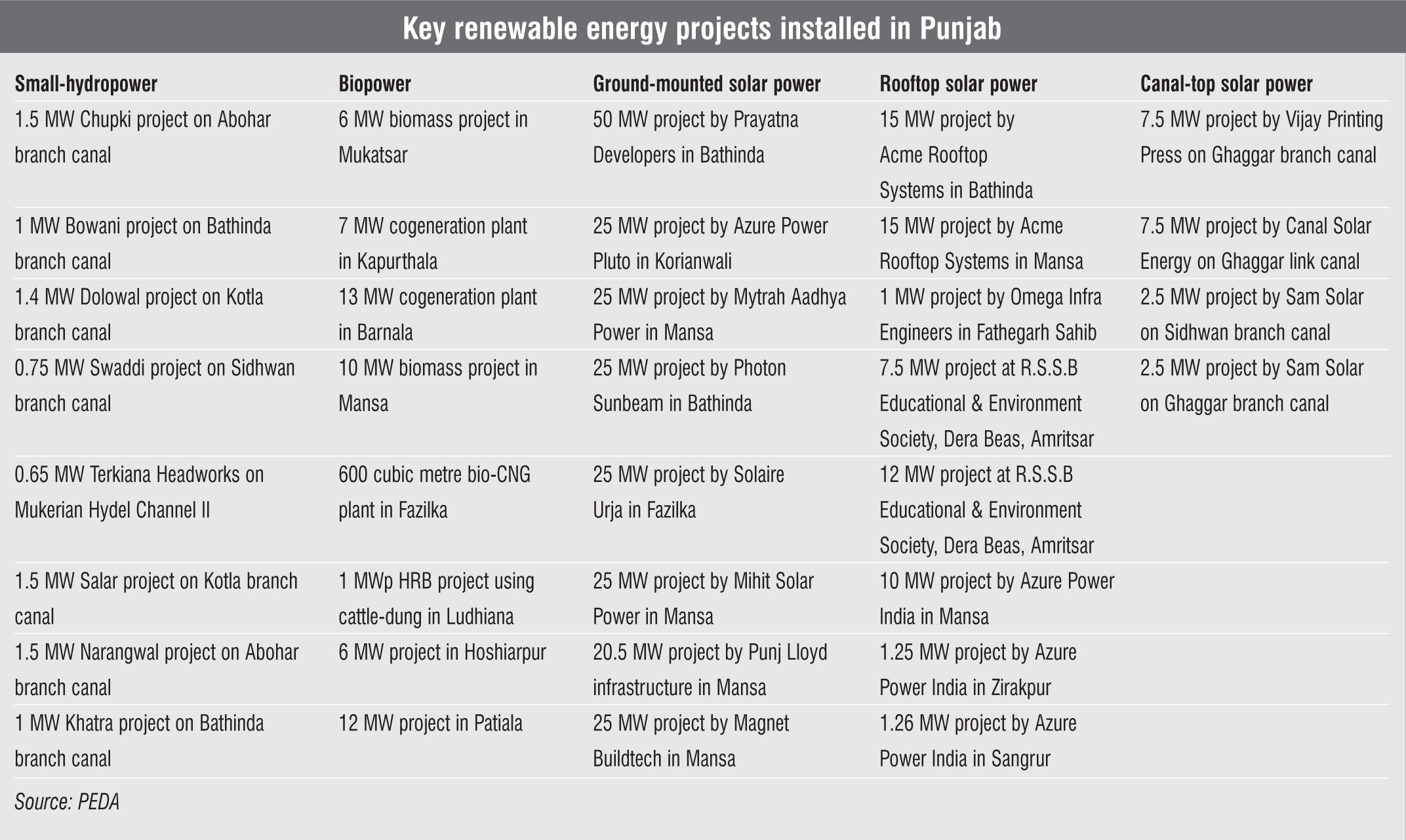

From just about 9 MW in 2013, Punjab has increased its installed solar power capacity by almost 100 times in a span of five years. The small state in north India has 905 MW of installed solar power capacity, as of October 2018. This impressive growth in solar power capacity can be largely attributed to the state government’s initiatives to promote the ease of doing business. Apart from solar power, biopower and small-hydro power have seen significant investments in recent years. Punjab has installed 173.55 MW of small-hydro and 326.35 MW of biopower capacity as of October 2018.

The major advantage for interested developers is the provision of a single clearance mechanism, with one-time submission of the online application and documents as outlined in Punjab’s New and Renewable Sources of Energy (NRSE) Policy, formulated in 2012. The NRSE Policy offers several fiscal and non-fiscal advantages to developers including exemption from electricity duty, external development charges or change of land use charges, stamp duty for land registration and land lease, and parallel operation charges. It also eases the process of pollution clearances and land acquisition.

Apart from the NRSE Policy, the state has a robust intra-state transmission infrastructure in place, and well developed roads and railway networks. These have created a favourable investment and development environment in the state. For its efforts, Punjab was even awarded the best performing state award in renewable energy capacity building at the inaugural session of the First Renewable Energy Global Investors’ Meet and Expo in 2015.

Potential and targets

Punjab receives 330 days of sunshine with a high solar insolation estimated at 4-7 kWh per square metre. The state’s total solar potential is estimated at 4.8 GW, of which rooftop solar accounts for 2 GW and ground-mounted solar for the remaining capacity. With 21 million tonnes of agricultural residue per annum, Punjab has the highest biomass potential in India at 3,172 MW. In addition, the state has a bagasse-based cogeneration and waste-to-energy potential of 300 MW and 45 MW respectively. In fact, about 14 per cent of the country’s total biomass potential is in Punjab. The state’s water canal network of 5,000 km also allows for the development of several small-hydro projects. The small-hydro potential is estimated at 441 MW. To utilise its renewable potential, the state government has set a target to install 3,200 MW of solar power, 820 MW of biopower and 200 MW of small hydro power by 2022.

Punjab has negligible wind power potential at lower heights as proved by earlier wind resource estimates. However, the state government is keen to determine wind potential at hub heights greater than 100 metres. To this end, the Punjab Energy Development Agency (PEDA) has signed MoUs with two private wind power companies to carry out these assessments and set up wind power projects in the state if a feasible potential is discovered.

Solar power uptake

Since most of the land in Punjab is fertile and can be used for agriculture, the available land area for solar PV deployment is limited. Hence, the state government is promoting large-scale rooftop solar projects and canal-top solar projects, and has tendered large capacities for the same. In fact, the state has the largest rooftop solar plant in the world. This 12 MW solar power project is located at the Radha Soami Satsang Beas Educational and Environmental Society, Punjab.

Punjab has net metering, gross metering and captive metering policies for promoting rooftop solar deployment in the state. Under the net metering policy, the rooftop solar power generated by consumers is first used to meet the requirements of the building and the surplus power is fed into the grid of Punjab State Power Corporation Limited (PSPCL). Under this policy, the consumer gets a bill for the net power consumption after the adjustment of the import and export of power. Like net metering, under gross metering, solar power is generated through rooftop systems and is fed into the grid of PSPCL by the generator at a tariff fixed by the Punjab State Energy Regulation Commission (PSERC). Under captive metering, solar power is generated and consumed on the consumer premises without any export of power to the grid.

Punjab has more than 1,500 MW of solar canal-top potential. However, till date, only 20 MW of such projects have been commissioned by PEDA. Two projects of 7.5 MW each were commissioned on the Ghaggar branch canal and the Ghaggar link canal in March 2018, and two projects of 2.5 MW each were commissioned on the Sidhwan branch canal and the Ghaggar branch canal.

Deployment of biomass projects

Punjab has a huge untapped bienergy potential. The biopower segment has not picked up pace like the solar segment due to certain inherent issues. Though biomass residue is generated in large quantities every year, its availability is seasonal and limited to two or three months of harvest. Thus, maintaining a consistent supply is challenging. In addition to this, the cost of storing and transporting biomass residue over long distances becomes economically unviable for developers.

Another key constraint is inconsistencies in the price of biomass residue. With industries migrating to biomass from coal or oil, farmers have hiked the feedstock price. There is a dearth of long-term agreements between farmers and developers, and middlemen have to be engaged for such partnerships, which is another added cost. Punjab has been making consistent efforts to promote the biopower segment. To instil confidence among developers and address some of their issues, PSERC has been notifying tariffs for biomass each year. It is one of the few states to do so.

In November 2018, PSPCL initiated the revival of a 10 MW biomass power plant. The project, located in Jalkheri, is being revived on a renovate-operate-transfer basis. It is likely to become operational after 27 months from the date of signing the lease agreement, while the lease agreement is likely to be signed within 45 days of the issue of letter of award. Once operational, the project will not only consume about 80,000 million tonnes per annum of rice straw for producing electricity, but will also save the environment from getting polluted.

Power purchase and discom status

Power purchase and discom status

Given the invester-friendly business climate of Punjab, most of the renewable energy projects in the state are being set up by private developers on a build-own-operate basis. These projects have power purchase agreements for 25 years with letters of credit and escrow payment security mechanisms. To bring respite to developers who have been suffering from payment delays across India, PSPCL clears its dues within 60 days.

Unlike many other state discoms, PSPCL has low aggregate technical and commercial losses. It files its tariff petition in a timely manner and has an operational fuel and power purchase cost adjustment framework, which allows for the increase in the cost of “uncontrollable items” to be recovered from consumers on a quarterly basis. Hence, PSPCL has been awarded a B+ rating in the Ministry of Power’s Sixth Annual Integrated Rating of state distribution utilities submitted by ICRA Limited and Care Analysis and Research Limited. In order to comply with its present solar-renewable purchase obligation (RPO) targets, PSPCL is planning significant capacity additions of 1,000-1,500 MW through solar ground-mounted systems. The state is also in the process of revising its RPO targets.

In April 2018, PSERC issued draft regulations for the forecasting, scheduling and deviation settlement of energy generated through solar and wind power projects. As per the regulations, the minimum capacity of each project should be 5 MW, which should be connected to the intra-state transmission system. These regulations are also applicable to solar and wind power plants generating energy for captive use or for sale within or outside the state. Under these regulations, all wind and solar project developers have to appoint a qualified coordinating agency to perform meter reading, data collection and communication. While the regulations will come into effect on the day they are published in the state’s official gazette, forecasting and scheduling will become effective three months from the date of notification. PSERC plans to issue a separate notification to make the commercial deviation settlement mechanism operational.

Apart from rooftop solar and solar canal top projects, the state government is exploring the possibility of deploying solar power plants on agricultural land. These solar plants will be developed by private parties for a minimum lease period of 25 years, and the farmers will be allowed to simultaneously cultivate their land by growing fruits and vegetables. To this end, the Punjab government, in July 2018, approved a pilot solar PV project to be developed on agricultural land in the state.

This pilot project is a result of the findings of the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII). CII found that several private solar power developers are interested in setting up solar power projects on farm lands leased for a tenure of 25 years. The state government is looking to set up such projects in the Kandi area and in southwest Punjab, especially in the citrus orchards and the vegetable-growing belt near Ludhiana and Malerkotla.

Outlook

Apart from its own solar power, biopower and small-hydro projects, the state discom is going to procure wind power through the interstate transmission system (ISTS). The state discom signed a power sale agreement with the Solar Energy Corporation of India (SECI) in December 2017, to procure power from its ISTS-connected wind projects. These wind projects will be set up under SECI Tranche-II wind auctions.

These initiatives by the state government and agencies to procure greater renewable energy will help the state in achieving its RPOs and reduce its dependence on thermal power. However, the state has a lot of ground to cover in terms of its solar power targets, with just one-third of the target capacity met until now. Going forward, the state needs to focus on tendering larger solar power capacities. With a robust policy mechanism and implemention framework already in place, these large auctions will drive solar power deployment and help the state meet its targets in time.