An exquisite example of modern architecture and urban planning, Chandigarh city, designed by legendary architect Le Corbusier, now has an added feature – a series of blue solar panels atop many prominent buildings, right from the interstate bus terminal (ISBT) as one enters the city. The first planned city of the country, Chandigarh is now all set to become India’s first model solar city.

The Master Plan to develop Chandigarh – the capital of Punjab and Haryana – as a solar city was given the go-ahead in 2012. While over the past few years initiatives to go solar have started picking up pace, there are challenges that need to be overcome. Situated at the foothills of the Shivalik mountain range, Chandigarh does not have its own conventional power generation facility and is dependent on neighbouring states for its electricity needs. Also, except for tapping solar power, the city hardly has any other source of renewable energy. As a planned city, Chandigarh is already developed and there is not much vacant land available; therefore, the thrust of harnessing solar power has been on rooftop solar photovoltaic (PV) installations.

According to the Chandigarh Renewal Energy and Science & Technology Promotion Society (CREST), the nodal agency for the implementation of the Master Plan, an aggregate capacity of 11 MWp of grid-tied rooftop solar plants has already been installed against the mid-term target of 5 MWp for 2017. The initial long-term target of 10 MW of capacity installation envisaged in the Master Plan has since been raised to 50 MW by 2022 in line with the revised power tariff policy of 2016 and efforts are on to achieve the target within the stipulated time frame. Around 230 buildings in Chandigarh have rooftop solar PV plants, including 36 in the private sector. As per figures available till April 30, 2017, Chandigarh has generated 20.36 MUs of solar energy on the rooftops of government buildings in the past three and a half years.

CREST has also taken the solar initiative to educational institutes across the union territory. Of the 114 government schools in Chandigarh, 75 already have rooftop solar PV systems in place and the rest will be covered during this year. Meanwhile, all 13 government colleges have rooftop solar PV installations. In fact, one of the largest rooftop solar PV plants in Chandigarh, of 1 MWp capacity, was installed and commissioned at Punjab Engineering College in 2015. A number of private schools and colleges have also approached CREST for the installation of rooftop solar PV systems. Panjab University in Chandigarh, spread over an area of 550 acres, has a solar power generation potential of 7.5 MW. However, according to CREST sources, the university is yet to take a call on developing this capacity.

In an important initiative towards accomplishing the goalpost of a “model solar city”, last year, the Chandigarh administration made the installation of rooftop solar PV systems mandatory for residential and non-residential buildings on 500 square yards and above. The order mentions the specific solar PV plant capacity that has to be installed depending on the land area and the building type. The response to this mandate has been lukewarm so far. Only about 1 per cent of the 7,600 building owners have complied with the order. One of the reasons cited is the lack of any provision for punitive action for non-compliance.

According to Santosh Kumar, chief executive officer, CREST, an aggressive campaign has been launched to sensitise the people, by holding seminars, meetings and interactive sessions with all stakeholders including residents, solar equipment suppliers and bankers, and creating awareness through the media. Kumar is hopeful of a positive response from the people to the mandatory installation of solar PV systems. The biggest challenge, he says, is the fact that while electricity is available at a rate of over Rs 5 per kWh, the cost of production of solar power comes to Rs 6.50 per kWh, but he hopes that things will change for the better once the production cost of solar power comes down.

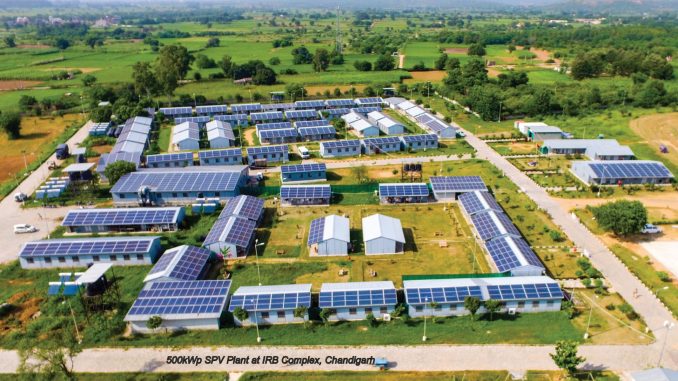

The incentives include a 30 per cent subsidy for the installation of rooftop solar PV plants. Consumers also have the option to sell solar power to the grid through net metering and gross metering. Net metering has the export-import feature, wherein consumers can generate solar power for their own consumption and feed the excess power to the grid. In gross metering, the consumer can directly sell the power generated to the grid through the discoms. Entities that have not taken any subsidy can sell the power at the rate of Rs 8.57 per kWh fixed for the current year, and there are different rate slabs depending on the percentage of subsidy and capacity of the solar power plant. The electricity bills of government schools and colleges that have opted for net metering are adjusted accordingly after taking into account the surplus units fed into the power grid. CREST itself is earning revenue from three of its projects – two installations of 300 kW each at ISBT in Sector 17 and the Indian Reserve Battalion complex, and another 200 kW solar plant at ISBT in Sector 43. CREST has received a 30 per cent subsidy for these projects, and is getting Rs 6.66 per unit for selling the power directly to the discom.

However, the ambitious 25 MW solar power plant on Patiala ki Rao, a seasonal rivulet, is yet to take off. The plant – the biggest in the city – would be crucial to achieving the target of 50 MW of installed generation capacity by 2022. However, it has been hanging fire since 2015. The spadework to get the project rolling is on and a meeting was recently held in this connection. Kumar is confident that the project will be completed over the next two to three years.

Another target in the Master Plan is to set up large solar energy-based generation projects at landfill sites. However, this too is yet to be started. Some IT units as well as the printing press of a newspaper have installed solar PV systems. About 400 solar street lights have been installed in gardens and parks and by cooperative societies. The mandatory use of solar water heaters is largely being followed in hotels, hospitals, etc., but the scope of these systems is limited in residential areas. In addition, there is a potential to install 7 MW of solar power capacity by the municipal corporation for waterworks.

The winner of several national awards, CREST has taken several innovative measures to harness solar power. A floating solar power plant pilot of 10 kWp was commissioned at Dhanas Lake last year. The power generated is consumed there itself for aeration and the running of two fountains. Owing to the dual-axis tracking technology deployed, 30 per cent more power is generated than that by a conventional ground-mounted solar PV system. The project is the first of its kind in Chandigarh.

About three years back, a 15 kW solar PV installation atop a cycle stand was commissioned and two more are in the pipeline. These small initiatives may not add much in terms of power generation, but they do send a powerful message on the importance of harnessing power from sunlight, which is available for 300 days in a year, and the need to reduce the dependence on conventional sources of energy.

As of now, only a little over one-fifth of the 50 MW target has been achieved, but the momentum is building up and CREST is hopeful that, with the incentives and other measures being taken, it will be able to cover the gap by 2022. Kumar, however, is of the view that a true solar city can only be built when every household has a rooftop solar PV system.