Solar power tariffs hit a historic low of Rs 2.44 per unit in the 500 MW Bhadla Solar Park auction. This article analyses the viability of these tariffs and the future outlook for the solar segment.

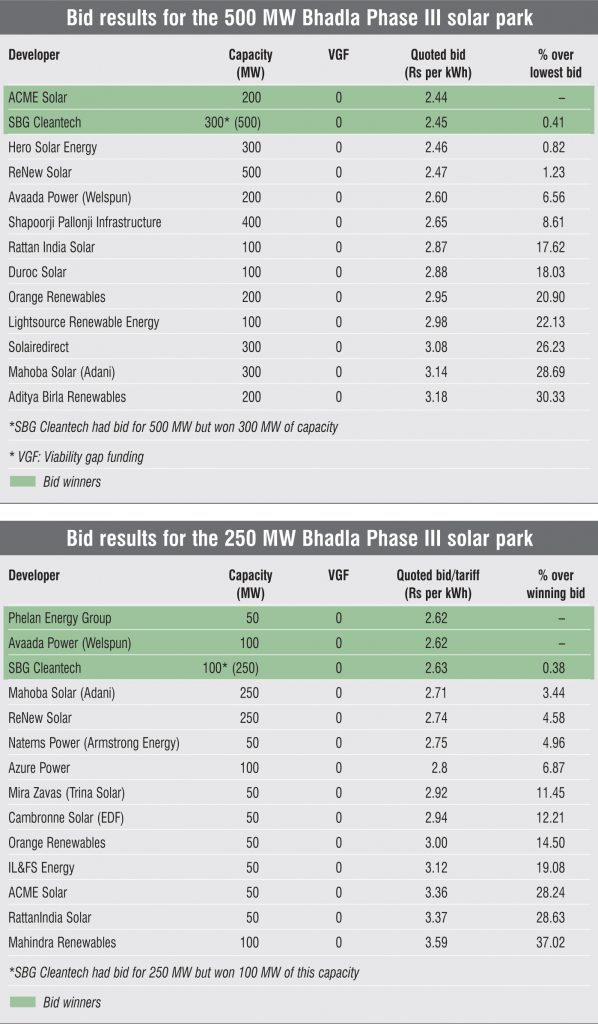

Speaking at Renewable Watch’s “Solar Power in India” conference in July last year, Rohit Modi, chief executive officer, solar business, Suzlon, had said, “Solar tariffs in India will not be more than Rs 3 per unit by 2020 and not more than Rs 2 per unit by 2025.” At the time when the lowest solar tariff of Rs 4.34 per kWh for the Bhadla Solar Park Phase-II was being seen as an outlier, Modi’s forecast of Rs 3 per unit seemed highly improbable and was contested by the majority of the participants. But, less than a year later, the solar power tariff has already hit a new historic low of Rs 2.44 per kWh. This tariff was quoted by ACME Solar in the auction for 500 MW of capacity at Bhadla Solar Park Phase-III and, interestingly, this bid is not an outlier. The remaining 300 MW capacity was won by SBG Cleantech at Rs 2.45 per kWh. The companies that closely missed the cut were Hero Solar, which quoted Rs 2.46 per kWh, and ReNew Solar, which quoted Rs 2.47 per kWh.

What is even more noteworthy is the frequency and scale of tariff decline in the industry. The Rs 2.44 per kWh bid achieved on May 11, 2017 is 7 per cent lower than the previous low of Rs 2.62 per unit achieved on May 9, 2017 during the auction of 250 MW of capacity for Bhadla Solar Park Phase-IV. In March 2017, the levellised solar power tariff dropped to

Rs 3.15 per unit in the auction for a 250 MW project in Andhra Pradesh’s Kadapa Solar Park. In February, lower capital expenditure and cheaper credit brought down the solar tariff to Rs 2.97 per unit for the first year of operation in the auction conducted for 750 MW of capacity at the Rewa Solar Park in Madhya Pradesh.

These developments raise a number of questions. What led to the sub-Rs 2.50 per unit tariff? What does it mean for the overall electricity market in India? How will it impact the demand for conventional power by discoms? And where are the tariffs headed? Before dwelling on the larger issues pertaining to the changing energy mix, it is important to examine the latest bid results in detail.

Seven per cent decline in two days

Although solar insolation and component prices did not change much in two days, the tariffs still fell by 7 per cent. The size of the winning project at the Bhadla Solar Park Phase-III was definitely larger, but all the other aspects were the same as those in Bhadla Solar Park Phase-IV.

This 7 per cent decline is, therefore, owing to two key factors. First, the competition for new solar projects in the country is getting fiercer as the global solar equipment market is facing a glut, resulting in a price erosion. Moreover, the domestic supply of new projects is falling short of the demand. A large number of domestic and international players with voracious appetites and hefty investment plans have entered the solar space in the past year. Given the supply-driven nature of the solar market, these players are going all out to win whatever capacity is up for tendering. The soaring competition is apparent from the level of participation in the latest auction, wherein a total of 33 developers submitted bids for an aggregate capacity of 8,750 MW. This represents an oversubscription of almost twelve times compared to the 750 MW (500 MW + 250 MW) available for allocation. Of these, only four companies – ACME Solar, SBG Cleantech, Phelan Energy and Avaada Power – managed to make the cut.

Second, the entry of foreign firms and a number of domestic players, which have access to a large pool of low-cost funds, has also helped script India’s solar story. Take, for instance, the case of ACME Solar. It won two big projects, 250 MW at Rs 3.30 per kWh in the Rewa Solar Park auction in February 2017 and 200 MW at Rs 2.44 per kWh in the Bhadla Phase-III Solar Park auction in May 2017, recording a 26 per cent tariff drop in three months. The group raised Rs 5 billion in November 2016 from Piramal Enterprises and Dutch pension fund APG Asset Management NV. The proceeds were used to buy out EDF Energies Nouvelle and EREN Energies, which held 25 per cent stake each in ACME Solar.

The second big winner, SBG Cleantech, won a 100 MW project in the Bhadla Solar Park Phase-IV auction at Rs 2.63 per kWh and a 300 MW project in the Bhadla Solar Park Phase-III auction at Rs 2.45 per kWh, a 7 per cent difference. SBG Cleantech is a joint venture of the SoftBank Group, Foxconn Technology and Bharti Enterprises, and has access to low-cost funds from SoftBank. The venture was set up in June 2015 after SoftBank’s Masayoshi Son pledged to invest at least $20 billion in solar energy projects in India.

The other two winners were South Africa-based solar power developer Phelan Energy and Avaada Power, which quoted the lowest winning bids of Rs 2.62 per kWh for 50 MW and 100 MW capacity respectively under the Bhadla Phase-IV tender. These auctions mark Phelan Energy’s entry into the Indian market. Avaada Power is promoted by Welspun’s Vineet Mittal and this is his second innings in the country’s renewable energy space after Tata Power bought the entire 1.1 GW renewable portfolio of Welspun Energy for $1.4 billion in 2016.

A similar script of low bids was followed for the 750 MW Rewa Solar Park project in Madhya Pradesh and NTPC’s 250 MW plant in the Kadapa Solar Park in Andhra Pradesh. While Solenergi Power, Actis LLP’s green energy platform in India, was among the winning bidders for the Madhya Pradesh project by quoting a tariff of Rs 3.30 per kWh France’s Solairedirect SA won the rights to set up a 250 MW solar plant at Kadapa and sell power to NTPC at the previously recorded low tariff of Rs 3.15 per kWh. The other overseas firms active in the Indian solar energy space are France’s Engie, Italy’s Enel, Canadian Solar and Singapore’s Sembcorp. Their aim is to take advantage of the country’s growing green economy, which is being fuelled by the government’s ambitious clean energy goals. India plans to generate 175 GW of renewable energy by 2022. Of this, 100 GW is to come from solar projects.

Low risk, low returns

The declining tariff trend is good news for consumers as well as utilities. While the former will have access to cheaper power, utilities will benefit from an increased profit margin. However, for investors, project viability and returns will be adversely impacted. What then is driving developers and investors to engage in price wars that will only erode their profits?

Factors such as the fall in domestic debt costs by up to 1 per cent per annum in the past year (equivalent to a tariff reduction of approximately Re 0.10 per kWh), higher irradiation at the Bhadla Solar Park (equivalent to a tariff reduction of Re 0.15 per kWh), lower solar park charges (equivalent to Re 0.05 per kWh), participants’ healthy balance sheets and access to low-cost foreign capital, and relatively stronger rupee explain the low-cost of project development and hence lower tariffs. In addition, the Solar Energy Corporation of India’s (SECI) improved credit rating of double A plus ensures lower risk as far as power offtake is concerned.

The fact that investors are comfortable with the low returns at these tariff levels implies a growing focus on low-risk projects and patient capital, which brings modest yields over time. The only counterpoint here is that module prices declined by 30 per cent during the past year and developers seem to be counting heavily on another fall of about 23 cent per watt-peak in the next 10 months. Although module industry dynamics remain benign, it seems a very bold call to price bids assuming the base case scenario. A low-risk, low-return model also implies that India is no longer a market for smaller players who find it difficult to access low-cost finance. If small developers have to stay in the game, they will need to rethink their strategies or redefine their business model.

What next

In terms of capacity addition, ideally, lower solar tariffs should boost the demand for solar projects. Ironically, they are leading to a short-term slowdown, with the central and state governments reconsidering the procurement policies. This has happened recently in the wind power space wherein Andhra Pradesh Southern Power Distribution Company Limited (APSPDCL) has decided to renegotiate the power purchase agreements (PPAs) that it had signed with 41 wind project developers for 832.4 MW of wind capacity. The PPAs were signed before the country’s first wind power auction was held, which saw the tariff drop to Rs 3.46 per kWh. The state now wants to renegotiate the Rs 4.80 per kWh tariff quoted in the PPAs. A similar trend is likely to be witnessed in the solar segment as far as the ongoing tenders are concerned. Further, there may be a slight reduction in solar capacity addition in the coming year, before it picks up pace again 2019 onwards.

With the prevailing solar tariff trend, it should not be surprising to see a further decline in tariffs in upcoming auctions, where the factors may be even more favourable than those at Bhadla. However, the decline will not be registered across all types of tenders, especially in cases where the offtaker is not reliable. Take, for instance, the case of the Tamil Nadu Generation and Distribution Corporation (TANGEDCO), which recently announced a solar tender for 1,500 MW of capacity through reverse auction. TANGEDCO has set the upper tariff limit at Rs 4 per kWh. Given the trend so far, it could have comfortably set it at Rs 3 per kWh. However, given the fact that TANGEDCO does not have a good reputation regarding payments and curtailment issues, this upper limit is not feasible for many developers as it raises the risk level. Of the total tendered capacity of 500 MW in February 2017, TANGEDCO received bids to develop just 117 MW. It had tendered another 500 MW of solar capacity in November 2016 to meet its renewable purchase obligation but received technical bids to develop only 300 MW.

Thermal lags behind

An interesting fact to note is that all the recently determined tariffs are lower than Rs 3.20 per unit, the average rate of power generated by coal-fuelled projects of India’s largest power generation utility, NTPC. This raises questions regarding the impact of the declining solar tariffs on the overall electricity market, including the energy mix, thermal power tariffs and discom behaviour. “Such low tariffs are obviously fantastic news both for discoms and end-consumers,” says Vinay Rustagi, managing director, BRIDGE TO INDIA. If solar power keeps on growing sustainably (that is, if storage solutions become viable in a few years to address the intermittency challenge), it would mean that the power sector is looking at long-term deflation, which would be revolutionary for the entire energy industry and disrupt many businesses. “Thermal power will be badly hit. We have already seen that many discoms have cancelled or downsized their thermal power procurement plans,” Rustagi adds.

If solar capacity grows at the anticipated pace, the operation of conventional plants will have to be ramped down or up for maintaining the demand-supply balance. This would result in a lower plant load factor for conventional power stations, which is expected to drop to 50 per cent from the current 60 per cent. This, in turn, would push up the fixed cost component in the average cost of power and put coal-based plants out of favour with discoms. But a section of industry players caution that there are a number of hidden costs in solar power costs. The cost of integrating such large-scale solar power into the grid should be considered when calculating the landed cost. According to experts, grid-connected solar PV plants use transmission lines only 20 per cent of the time compared to 70 per cent by traditional plants, which makes it 3.5 times costlier to wheel solar power.

Massive land requirements to erect solar panels amplify the issues further. According to the Central Regulatory Electricity Commission’s tariff estimates, a 1 MW solar PV power plant needs around 2.5 acres of land. However, owing to the fact that large ground-mounted solar PV farms require space for other accessories, the total land required for a 1 MW solar PV power plant would be around 4 acres. So investment in solar power must take into account a mammoth hidden cost. Further, some experts argue that the sector enjoys various incentives and exemptions that have been provided to promote the uptake of solar. Rustagi, however, does not agree with this. “Many incentives and subsidies (such as VGF, rooftop solar subsidies for business consumers and a 10-year tax holiday) have been given to the sector historically, but these are being phased out as the sector does not need them any more. Some benefits like accelerated depreciation (which was reduced by 50 per cent from April 2017) and free interstate transmission are likely to be phased out slowly. But it is important to remember that even coal and other sources of power receive many benefits. Coal in India is sold on a cost-plus basis. Moreover, the coal price (and thermal power price) does not factor in exogenous costs (pollution cost, depletion of the water table, impact on health, etc.),” he says.

Therefore, although concerns have been expressed about the sustainability of such low solar bids, the stage is set for a tariff correction for power from other fuel sources so that they remain relevant in the country’s energy mix.