This is an extract from a recent paper “Hydrogen in China: Why China’s success in solar PV might not translate to electrolyzers” by Oxford Institute for Energy Studies.

China’s manufacturing prowess and progress in lowering electrolyzer costs have raised hopes – and concerns – about its potential to lead electrolyzer manufacturing and exports globally, accelerating the clean energy transition worldwide. The dramatic cost reductions achieved in solar photovoltaics (PV) and China’s subsequent dominance of these supply chains are often cited as an example of how things might play out in the hydrogen space. This paper explores whether China can replicate its success in solar with electrolyzers, considering government support, learning rates of PV and electrolyzers, Chinese corporate strategies, and the external environment for exports.

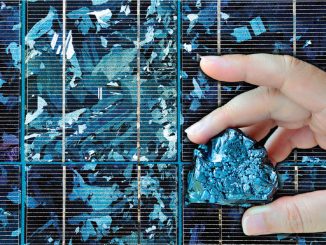

Development of Solar PV in China

The development of China’s solar PV industry can be divided into four stages: In the first two stages, Chinese companies were active in the labour-intensive mid-stream. This was driven by the huge demand for solar PV products in Europe, enabled by technology transfer from industrialized countries (such as Germany, Australia, the US, and Canada) and by local government support. But Chinese companies were weak in the upstream sector, specifically in the manufacture of purified polycrystalline silicon which was dominated by foreign companies. Manufacturing solar cells was therefore costly. Starting in 2009, in the face of decreasing exports, anti-dumping investigations issued by the EU and US, and the global financial crisis, the Chinese government began to help the solar PV industry shift from an export-oriented manufacturing industry to one fulfilling the domestic deployment of solar, and issued policies on market consolidation and technology advancement to foster the domestic solar market. Solar PV’s initial phase featured start-ups and basic policy support for an emerging export product. The development of China’s solar PV industry between 1970 and 2004 saw the emergence of first-wave start-ups supported by local governments to capture external demand for solar PV products, despite general central support for renewable energy.

The early development of solar PV in China was boosted by privately owned enterprises (POEs), such as Suntech and Yingli, set up by experts who had returned from overseas with knowledge of modern green-energy technology, or having expertise in manufacturing scale-up. Local governments granted various forms of support to local solar businesses within their jurisdictions. However, it was the huge export markets for solar PV, such as Spain and Germany, that stimulated the development of China’s solar PV industry. From 2004 to 2008, the manufacturing of solar cells experienced a ‘wild growth’ phase, increasing from 50 MW per year of production volume in 2004 to 2000 MW per year in 2008. In parallel, China’s share of the global PV cell market share rose from less than 1 per cent in 2004 to nearly 45 per cent in 2008. Industry development in this phase was enabled by a number of factors. The surge in demand for PV in Europe also spurred a rush of speculative investments by private companies to meet that demand. Chinese companies imported turnkey production lines, raw materials, and second-hand equipment. Solar POEs processed the imported purified polysilicon into wafers, cells, or modules for re-export. This, in combination with support policies in solar PV manufacturing, the country’s cheap labour, and Chinese companies reaping economies of scale in the manufacturing process led China to gain a competitive advantage in PV products. Around 95 per cent of solar PV made in China were exported to Germany and the US.

During the same period, the central government began to stress the strategic importance of the solar PV industry and to develop the domestic solar market. Although The 11th Five-Year Plan (2006) did not view the solar PV industry as an area for China’s industry upgrading, the Outline for National Middle and Long Term Scientific and Technological Development Plan (2006–2020) published by the State Council in 2006, and the Directory of High and New Technology Products (2006) issued by the Ministry of Science and Technology prioritized the R&D and manufacture of high-cost performance solar PV cells, modules, power controllers and inverters, along with their application technologies. By the end of 2007, the central government had identified the solar PV industry as a ‘high-tech industry’ which could help China restructure its national economy and enhance its overall industrial competitiveness. This increased the central government’s focus on the solar PV industry as a component to China’s industrial strategy. The emphasis on accelerating the industrial upgrading of the solar PV industry also prompted the central government to foster the domestic market for solar PV products. The scale-up of manufacturing and learning-by-doing in the fields of PV, along with deploying large-scale, grid-connected PV plants in China enabled costs to decline steadily, which in turn drove more widespread adoption of solar across China. By requiring grid companies to take renewable electricity and setting quantitative targets for solar power deployment, the Renewable Energy Law adopted in 2006 and the Mid-to-Long Term Renewable Energy Development Plan (2007) helped improve the domestic market for solar PV. Given central government support and the success at penetrating overseas markets, by 2007 more than half of all major Chinese cities had established PV industrial policy priorities or targets, viewing the sector as an opportunity for both growth and employment.

At the high-speed-development stage (2009–2018), the Chinese government strengthened its efforts to foster the domestic solar market and restructure the solar PV industry. These efforts were prompted by the desire to support the sector in the face of weaker international demand following the 2008–2009 financial crisis, the anti-dumping investigation on China’s solar panels after 2012, as well as the cessation of production and even the bankruptcy of several domestic solar companies since 2011. Policy actions included introducing the Large-scale PV Power Station Concession Bidding Programme, the Golden Sun Programme, and a generous feed-in-tariff for domestic PV projects. The newly-introduced PV feed-in tariff of up to around US$ 0.17/KWh was significantly higher than the average rate for coal-fired electricity (around US$ 0.05/KWh) and was thus expected by the government to incentivize investments in solar power generation. With the decrease of solar power prices, the Notice on Matters Related to Photovoltaic Power Generation (2018) was adopted to gradually reduce subsidies. Subsequently in 2019, the National Development and Reform Commission issued the Notice on Actively Promoting Subsidy-Free Grid Parity for Wind Power and Solar Power Generation, marking the beginning of the era of subsidy-free grid parity for solar power generation.

As production increased, the cost of solar modules per watt of capacity fell in China from $4.25 to $0.36 between 2006 and 2017. The conversion efficiency refers to the efficiency of transforming solar energy into electricity. For every 1 per cent increase in photovoltaic power conversion efficiency, the cost per kilowatt-hour decreases by 5 per cent to 7 per cent. The conversion rate of monocrystalline silicon solar cells has increased from around 18 per cent in 2012 to around 24 per cent in 2023. For China, as it looks to achieve its 2060 carbon neutrality goal, the main problem now is how to integrate solar power into power grids and how to best use decentralized solar power rather than how to reduce the cost of solar power. In sum, at the outset, before being recognized as an economic sector for fostering China’s industrial competitiveness, China’s solar PV industry primarily flourished as an export-oriented manufacturing sector. Its success can be explained by the transfer of mature and standardized turnkey manufacturing lines, by the external demand in the European Union that acted as a catalyst for the sector’s growth in China, and then by central government intervention for industry development and consistent support mechanisms implemented by local governments.

Development of Hydrogen in China

Whereas the solar industry started as a niche export manufacturing industry, China’s consideration of hydrogen as a fuel began as early as 1986 with R&D for hydrogen fuel cells with no consideration of the carbon footprint of hydrogen. Hydrogen development was an industrial strategy. The view was that promoting hydrogen fuel cell vehicles (FCVs) could help China in its new energy vehicles industrial strategy and reduce vulnerabilities related to the import of oil and gas. However, the complexity of hydrogen value chains and unclear applications limited progress in hydrogen technology development, resulting in little enthusiasm from the Chinese government. In 2006, the National Mid and-Long Term Development Plan of Science and Technology (2006–2020) saw efforts to develop other segments of the hydrogen value chain, and identified hydrogen storage and transport as an emerging energy technology. Because of expensive hydrogen technologies, this renewed interest did not lead to sustainable investment or scalable development in China. Between 2010 and 2014, the development of FCVs fell behind the development of electric vehicles due to factors such as insufficient technology development and the high costs of hydrogen infrastructure. During 2015 and 2019, there was a rapid development of FCVs, along with R&D for hydrogen production, storage and transport crucial for refuelling FCVs. This was likely due to China’s efforts to catch up with neighbouring countries like Japan and South Korea in FCV development, in part by introducing new subsidy regimes for purchasing FCVs.

Since 2020, policy makers have focused more on upstream hydrogen. Following China’s pledge, issued in 2020, to peak carbon emissions before 2030 and reach carbon neutrality by 2060, the hydrogen economy has received new emphasis, with renewable hydrogen and electrolyzers now a rising priority for Chinese policymakers. In 2021, more than 30 industrial policies issued at the central level incorporated guidance on hydrogen. The most important policy document so far in the hydrogen sector – the Mid- and Long-Term Hydrogen Industrial Development Plan (2022) – articulated the aims of improving efficiency of renewable hydrogen production and of scaling up the productivity of related production equipment, such as electrolyzers. More specifically, the 14th Five-Year Plan of Energy Technology Innovation (2021) set the objectives of improving technological capacities for manufacturing PEM electrolyzers and solid oxide (SO) electrolyzers.

Local government strategies have been mixed, with some emphasizing FCVs, and others electrolysis. Prior to the implementation of the Mid- and Long-Term Hydrogen Industrial Development Plan (2022), some local governments were already promoting innovation and the electrolyzer manufacturing, even though the emphasis remained on the development of hydrogen fuel cells. For example, Beijing and Changshu city, in Jiangsu province, are promoting the advancement of PEM and SO electrolyzer technology, while also seeking to improve the efficiency of alkaline electrolysis. Similarly, Ningbo city in Zhejiang province announced plans to support hydrogen equipment manufacturing for both alkaline and PEM electrolysis. Accordingly, similar to the electrolyzer markets of other states, which are dominated by PEM electrolyzers and alkaline electrolyzers, China is catching up in PEM electrolysis and continues to improve the performance of alkaline electrolysis.

Hydrogen strategies have a strong regional component, often linked to renewable resource availability. In response to this, the governments of cities or provinces with rich renewable energy resources have adopted hydrogen development plans. Most of China’s renewable hydrogen projects are located in Northwest China, Northeast China and North China, with Inner Mongolia having the most. According to the World Economic Forum, if the price of renewable electricity falls below 0.15 yuan/KWh, compared with the current average of 0.5 yuan/KWh, the production cost of renewable hydrogen can decrease from the current.9-42.9 yuan/kg to 15 yuan/kg within the current technological framework, making it possible to compete with fossil-fuel-based hydrogen. Already, some local governments relaxed the hazardous chemical regulations and allowed renewable hydrogen production outside chemical industrial parks.

Energy state-owned enterprises (SOEs) have played a significant role in large-scale, capital-intensive demonstration projects for renewable hydrogen production, both domestically and internationally. For instance, Sinopec has invested in a renewable hydrogen production project in Beijing using PEM electrolyzers, while the State Power Investment Corporation has made renewable hydrogen investments in Brazil, utilizing centralized solar and wind power generation facilities. Meanwhile several large private companies are investing in domestic renewable hydrogen production. Despite this, most private companies are investing in less capital-intensive hydrogen projects, such as the R&D and manufacturing of hydrogen-related equipment

Alkaline electrolyzer technology in China has become relatively mature with high localization rates for the key components, allowing this technology to be used in China’s renewable hydrogen projects. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), as of the end of 2022, known global electrolyzer manufacturing capacity reached 13 GW/year, half of which was located in China and an additional fifth in Europe. However, the deployment of electrolyzers in China only reached 800 MW in 2022, of which alkaline electrolyzers made up 776 MW , with only 24 MW of capacity constituting PEM electrolyzers. In 2023, only 1.5 GW of electrolyzer capacity in China was earmarked for domestic projects and exports, even though manufacturing capacity had increased by 23 GW. Manufacturing capacity now far exceeds deployment and is dominated by alkaline electrolyzers. If deployment fails to gather momentum and export options are limited, companies may reduce production.

The technological development of China’s PEM electrolyzers still lags behind leading economies such as the EU. For the key components for PEM electrolyzers, China still relies on imports of proton exchange membranes and precious-metal catalysts, whereas alkaline electrolyzers use domestically sourced materials and equipment. Furthermore, new policy measures and protectionist policies banning technology transfer and international trade for high-tech equipment could limit the development of PEM electrolyzers in China. Still, the Chinese government is seeking to promote R&D and demonstration projects for PEM electrolyzers, despite concerns about import dependence, suggesting that for now it is prioritizing electrolyzer development over technology independence.

Comparing China’s hydrogen and solar development trajectories

Despite the long history of hydrogen development in China, its official recognition as a strategic emerging industry in 2016 marks a turning point and coincides with the inception of the domestic electrolysis industry. Since then, the development of renewable hydrogen in China has been driven by the central government’s ambition for industrial upgrading, by cheap renewable electricity prices, by the urgency of the energy transition, and by local governments’ ambition to take leading positions in developing the domestic industry. Both SOEs and POEs are playing important roles at this early stage of development with the Chinese government now also seeking international cooperation in hydrogen. So, even though both solar PV and hydrogen have benefitted from government support, it is important to unpack the drivers and nature of these support mechanisms. In the early stages of solar PV and electrolyzers – defined as 1997 to 2004 for solar and 2016 to the present for electrolyzers – both sectors benefitted from supportive policies for manufacturing at the local level and broader development of industry.

The solar PV sector was designated as a strategic emerging industry during the third stage of its development, roughly from 2009 to 2018, and relatively late on in its development. This designation matters because a ‘strategic emerging industry’ is considered central to China’s industrial upgrading and its core competitiveness and as such, receives significant state support. Even though the concept of ‘strategic emerging industry’ was first articulated in The Decision on Accelerating the Foster and Development of Strategic Emerging Industries (2010), support for such ‘high-tech industries’ had already started in the 1990s. But it was only in 2007, in light of the increasing maturity of the solar PV industry, growing attention to global demand for clean energy, and the economic strategy of developing domestic markets in all economic sectors that it was deemed critical to China’s economic development and then incorporated in the ‘strategic emerging industries’. In contrast, renewable hydrogen production was classified a strategic emerging industry by the central government in 2016, during its early stages. China’s electrolyzer manufacturers are perceived to be part of the national effort to develop green industries. This implies that funding will be allocated to the R&D of hydrogen technologies, that supportive policies will be adopted to incentivize investments, and that international cooperation is welcome. Moreover, The Energy Law of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) states that the Government will actively develop hydrogen. This provision lays a legal foundation for China’s development of hydrogen and has significantly boosted domestic confidence in the hydrogen business.

Private start-ups took a leading role in driving cost reductions for solar PV during the early stages, whereas hydrogen is dominated by large SOEs and bigger renewable players. The commercial landscape for renewable hydrogen in China is complex. SOEs are leading investors in renewable hydrogen production but POEs are playing a crucial role in cost reductions for electrolyzers. The different commercial landscape is likely related to the technological characteristics of solar PV and hydrogen and to the nature of China’s energy economy. While POEs have been crucial players in manufacturing – with contributions from foreign investors – SOEs dominate China’s energy sector and are critical in developing strategically-important, large-scale energy infrastructure. From 1997 to 2004, solar PV developed as a manufacturing industry and did not require the construction of largescale infrastructure, providing opportunities for POEs and foreign companies.

In the initial phases, most renewable hydrogen projects are located in North China where renewable electricity prices are low, because electricity costs are a significant component of the overall cost of renewable hydrogen production. Similarly, the solar PV industry was first developed in locations where local governments were highly supportive, offering tax incentives and low electricity prices for manufacturing, and close to abundant resources of primary industrial silicon. In sum, while both solar PV and renewable hydrogen projects benefitted in the early stages from local government support and being developed in proximity to key inputs, there are inherent differences in their development trajectories: solar started as a niche manufacturing industry for export markets, dominated by private firms which received government recognition and support as a strategic industry only at later stages of development. Hydrogen, meanwhile, started as a strategic industry aimed at supporting China’s decarbonization goals. And while private firms are active in electrolyzer manufacturing, SOEs play a significant role in hydrogen deployment and development given the need for large infrastructure investments, which are harder for private actors to undertake.

Access the paper here