As the curtains came down on COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, the global community stood at a crossroads, grappling with the progress made and the challenges yet to be overcome. The pledge to mobilise $300 billion annually for developing nations by 2035 was abysmally low and came as a disappointment, highlighting the persistent financing gap. Against this backdrop, the energy landscape is undergoing a tectonic shift, drawing attention to the way nations generate and consume power.

In the European Union, greenhouse gas emissions fell by an impressive 8 per cent in 2023, primarily due to reductions in the energy and industrial sectors as fossil fuel dependency declined. According to the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) World Energy Outlook 2024, fossil fuels such as coal, oil and natural gas are expected to peak before 2030, marking a turning point for the region. For the first time, wind and solar energy surpassed fossil fuels in the EU’s electricity mix, accounting for 30 per cent of electricity generation in the first half of 2024, according to a report by EMBER.

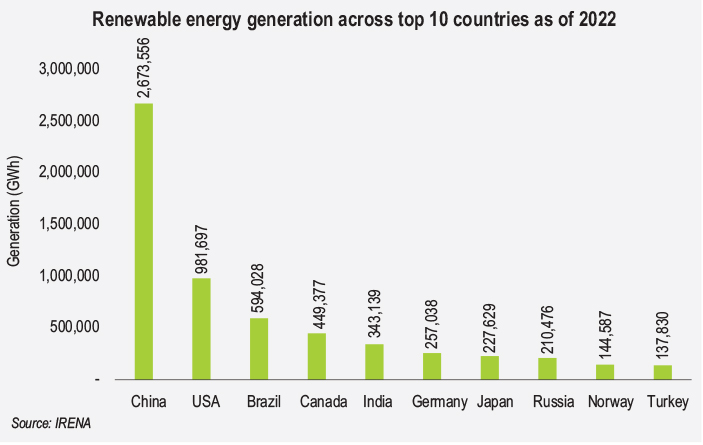

Globally, renewable energy now commands the largest share of power generation, with countries such as Brazil and China leading in hydroelectric and solar production respectively. This growth is mirrored by Asia’s impressive expansion in renewable energy capacity, as highlighted by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), which has shown an increase from 633 GW in 2014 to 1,959 GW in 2023. While Europe and North America have made steady progress, Africa and the Middle East continue to lag, reflecting the uneven pace of transition across regions. This disparity is further underscored by the IEA’s World Energy Investment 2024 report, which forecasts global energy investments exceeding $3 trillion for the first time, with two-thirds allocated to clean energy. However, only 15 per cent of this investment flows to emerging markets outside China, highlighting the persistent inequities in the global energy transition.

As nations navigate energy demand, geopolitical complexities and climate goals, renewables offer a pathway to a balanced and equitable transition. This article aims to provide an overview of the global renewable energy market as of 2024, highlighting key trends and developments that are shaping the sector…

Renewable energy growth and market trends

The global push for renewable energy has continued to gain momentum, with many countries implementing and acting upon transformative legislative and policy measures such as the Inflation Reduction Act in the US, the Energy Efficiency Directive in the EU, Japan’s revised Act on Rationalising Energy Use, and the latest cycle of India’s Perform, Achieve and Trade scheme.

Global investment in renewables surged by 20 per cent in 2023, reaching nearly $750 billion, equivalent to 1 per cent of the global GDP. Simultaneously, the total supply of modern renewables rose by 5 per cent year-on-year to almost 78 Joules (2.16 × 107 GWh), contributing 12 per cent to the global energy supply (IEA 2024). This growth reflects the phrase, “a rising tide lifts all boats,” as declining costs continue to enhance global competitiveness for the sector. In 2023, utility-scale solar photovoltaic project costs fell by 12 per cent, while onshore and offshore wind saw cost reductions of 3 per cent and 7 per cent respectively, according to IRENA’s Renewable Energy Production Costs Report. Battery storage costs have also plummeted by 89 per cent since 2010, reflecting significant advancements. As a result, compared to fossil fuels, solar PV and onshore wind are now 56 per cent and 67 per cent cheaper, respectively, marking a transformative shift from 2010 when solar PV was 414 per cent more expensive and wind was 23 per cent costlier.

As declining costs continue to lift the sector’s global competitiveness, one country stands out as the anchor of this rising tide: the People’s Republic of China. China’s leadership in renewable energy development is unparalleled, shaping market dynamics and driving down costs through large-scale adoption and innovation. The country continues to lead the global renewable energy market, accounting for 60 per cent of the capacity expansion expected by 2030.

For example, its Whole County PV Programme, launched in 2021, has accelerated distributed solar energy deployment, with cumulative solar capacity quadrupling and wind capacity doubling since the end of feed-in tariffs in 2020. China currently dominates electrolyser manufacturing, representing 60 per cent of global capacity and 40 per cent of investment decisions in 2023, driving down costs in a manner similar to its earlier success with solar PV and batteries. Japan, meanwhile, has maintained its leadership in rooftop solar deployment, which makes up 39 per cent of its total installed renewable energy capacity as of April 2024. These cost reductions have propelled the possibility of low-emission hydrogen production as global hydrogen demand reached 97 Mt in 2023.

With the rise of generative AI (GenAI), the energy market is also experiencing growing demand from data centres. According to a Goldman Sachs report, power consumption by data centres is projected to increase by 160 per cent by 2030, driven by the substantial energy requirements of AI technologies. Currently accounting for 1–2 per cent of global electricity usage, data centres could see their share rise to 3–4 per cent by the end of the decade. In the US alone, data centres are expected to consume 8 per cent of the country’s electricity by 2030, up from 3 per cent in 2022.

Innovations and opportunities in transition

The growing renewable energy market is also witnessing the rise of emerging technologies designed to address its inherent challenges of intermittency and unlock its full potential. Among these, the electrification of transport and advancements in battery energy storage systems (BESS) are reshaping the energy landscape. At COP29, energy storage was heralded as a cornerstone of renewable energy systems, transitioning from a supporting role to becoming the backbone of 24×7 renewable power. With the increasing adoption of electric vehicles (EVs), the integration of BESS is likely to play a crucial role in ensuring grid stability and reliability.

Carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS), although still a work in progress, has also emerged as a potential solution for reducing emissions in hard-to-abate sectors such as cement and steel, capable of capturing up to 99 per cent of carbon emissions. For instance, the Asian Development Bank, through its $100 billion climate finance commitment for 2019–2030, is backing major initiatives in CCUS across Asia and the Pacific. Notable among these is BP’s gas recovery and CCUS project in Indonesia, reflecting the growing appeal of this technology.

As AI emerges as a catalyst in the engine of progress, it is also transforming the renewable energy market with groundbreaking applications in optimisation and integration. The US Department of Energy’s Artificial Intelligence for Interconnection programme, supported by $30 million in funding, aims to address the significant backlog of 2,600 GW of proposed renewable energy projects awaiting grid connection. AI technologies, such as predictive analytics used at the Rewa Ultra Mega Solar Plant in India, enhance grid stability, minimise downtime and improve efficiency through real-time adjustments to turbine blades and solar panel orientations. The sector’s rapid adoption of AI is evident in its projected market growth from $214 billion in 2024 to $1,339 billion by 2030, according to MarketsandMarkets. In 2023 alone, $25.2 billion was invested in AI for renewable energy, nearly nine times the amount in 2022, highlighting its pivotal role in advancing the clean energy transition.

With emerging technologies reshaping industries, the principles of the circular economy have also gained traction, offering innovative pathways to repower renewable energy infrastructure. Solar panels and wind turbines are now being designed for extended lifespans, often operating beyond their intended 20–30 year durations. Offshore wind turbines, for example, can exceed their design life, reducing costs and enhancing reliability. Photovoltaic panels, which degrade by only 0.5 per cent annually, still generate over 80 per cent of their original output after 25-30 years, making their reuse and refurbishment far more cost-effective than decommissioning. These practices not only save materials and labour, but also help reduce greenhouse gas emissions and resource consumption.

Challenges in achieving targets

Why, despite global momentum, do we still face roadblocks in achieving renewable energy goals? The United Nations Emissions Gap Report highlights a stark reality: current efforts are insufficient to meet the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C target, demanding faster and more decisive action. One glaring challenge is the lack of transmission infrastructure and delays in grid connections which severely limit the expansion of renewable energy. Intermittency issues — where local wind or solar resources cannot compensate for shortfalls elsewhere — add to these constraints, further slowing progress.

Operational hurdles compound the problem even more. A shortage of skilled labour stalls the installation and upkeep of green technologies, while land acquisition remains a persistent bottleneck. Lengthy processes to secure titles and permits make the construction phase particularly fraught with delays and risks.

A glaring impediment to achieving climate targets — one that remains inadequately addressed and incompatible with the principle of Common but Differentiated Responsibilities — is the financial disparity faced by developing countries. At COP29, developing nations proposed $1.3 trillion annually starting 2025, primarily as grants, to address climate mitigation and adaptation. However, developed countries countered with an extremely low offer of $250 billion, later raising it to $300 billion by a token increase of merely $50 billion. This divide underscores the need for a “new financial architecture” as developing countries highlighted that the existing system, shaped during World War II (when most of these countries were not even independent), fails to address their unique challenges.

Further, the cost of capital varies widely across regions – while solar PV projects in the US may secure financing at rates as low as 3 per cent, similar projects in Brazil face rates as high as 12.5 per cent deterring investments in emerging markets. This entrenched financial imbalance remains one of the most significant barriers to achieving a truly equitable energy transition.

Geopolitical tensions also affect clean energy progress. While some election outcomes may accelerate clean energy adoption, others could hinder progress, delaying investments in large-scale projects that rely on stable policy frameworks. Geopolitical conflicts, such as those in Ukraine and West Asia, have further destabilised energy markets. Natural gas prices remain above the pre-crisis levels, and the risk of further disruptions persists.

Supply chain dependencies, especially on critical minerals, add another layer of complexity. According to the World Energy Outlook 2024 by the IEA, China produces over 80 per cent of the world’s battery cells, solar photovoltaic modules, and 65 per cent of wind nacelles. It dominates midstream processing of critical minerals, accounting for 65 per cent of global lithium processing, over 75 per cent for cobalt, and nearly all graphite anode production. Additionally, two-thirds of the world’s EVs are manufactured in China. These dependencies pose risks to supply chain security, particularly as geopolitical tensions between the US and China escalate. The geoeconomic conflict between the two countries underscores the importance of domestic coalitions that promote local manufacturing value addition in green value chains. Without such efforts, developing nations risk remaining export markets or resource colonies rather than active participants in the renewable energy economy.

Future outlook

Despite growing emphasis on climate finance, international public adaptation flows remain dominated by loans, putting financial strain on developing countries that are already reeling from economic stress. Debt conditionalities imposed by multilateral agencies further hinder efforts to balance austerity with renewable energy adoption. As Lee Harris notes in Phenomenal World, IMF policies in countries such as Pakistan, Mozambique and Indonesia undermine clean energy transitions by promoting coal investments and increasing climate-related financial risks in power sectors. While the IMF grants tax concessions for essential items such as food and health goods, renewable energy infrastructure is notably excluded, highlighting a stark contradiction between its actions and rhetorical support for clean energy. Without significant shifts in the financing structure, these nations may struggle to decarbonise industries and mitigate the catastrophic risks associated with climate change. Further, the path to a sustainable future must avoid displacing vulnerable communities in resource-rich regions such as Latin America or the Democratic Republic of Congo, where critical minerals are extracted. Investments in renewable energy and a just transition should not come at the cost of livelihoods or exacerbate socio-economic inequities. Industrial regulations and strategic collaborations between countries are critical to averting the impending climate crisis. Competitive subsidies and tariffs on solar panels or EVs risk escalating trade wars and burdening working-class communities with higher costs. Instead, fostering mutual cooperation to create green jobs and drive technological innovation is essential. The election of Donald Trump is likely to influence markets, potentially undervaluing clean energy companies, which analysts warn could slow down global progress. The way forward must prioritise industrial strategies that avoid such pitfalls and ensure inclusive economic benefits.

The geopolitical rivalry between the US and China remains a definitive challenge for the global energy transition. Both nations must prioritise building domestic coalitions that enable developing countries to participate in green value chains, rather than relegating them to the roles of resource suppliers or as export markets. The renewed Chinese investment in renewable energy projects in Africa, as highlighted during the 2023 Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), underscores the potential for strategic partnerships to drive climate cooperation. China’s decision to stop funding coal projects and its increasing focus on renewable energy in Africa exemplify the possibilities of collaborative approaches.

Hence, negotiations over technology transfer, market access and financial deals are central to the evolving dynamics of the global energy transition. Whether these efforts succeed will depend on the ability of major economies to foster inclusive frameworks that address the needs of the developing world. The future of the energy transition will be shaped not just by technological advancements or financial investments but by a shared commitment to mutual collaboration and equitable solutions. Like the rebuilding efforts of post-war economies, there must be a new “Green Marshall Plan” in a common pursuit of sustainability and climate justice to pave the way for a clean global energy landscape.