By Jaideep N. Malaviya, Managing Director, Malaviya Solar Energy Consultancy

By Jaideep N. Malaviya, Managing Director, Malaviya Solar Energy Consultancy

Ever since solar photovoltaic (PV) panels and cells were included under the E-Waste (Management) Rules vide a gazette notification of the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, effective April 1, 2023, they have generated a new vigour in the solar energy industry. The rules took due cognisance of the lack of infrastructure and certified recyclers, providing a 10-year period to stack scrap before mandatory extended producer responsibility (EPR) certificates need to be generated. As such, landfilling or disposing in unorganised sectors is banned, making recycling the ideal option.

This is a commendable move by the Government of India and is sure to pay rich dividends in the long term for business generation and employment opportunities. India is perhaps the second nation to do this, after the European Union’s Waste Electrical Electronic Equipment law for the safe disposal of solar PV panels and cells.

Building a circular economy

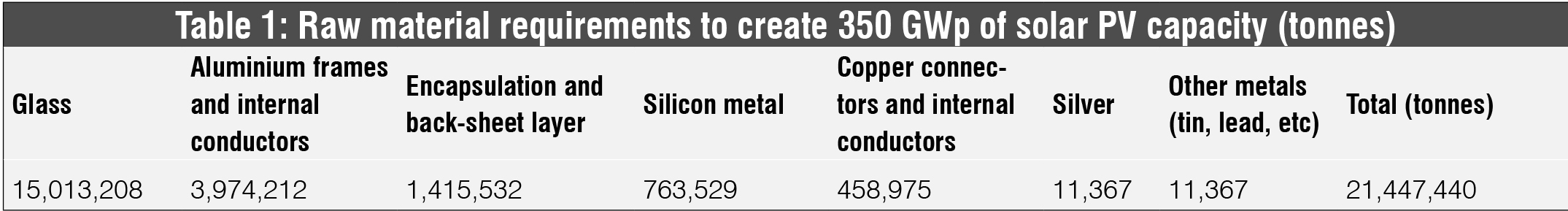

The Indian government has set the ambitious target of achieving 500 GW of non-fossil fuel installed capacity by 2030 as part of its net zero policy. It is expected that there will be 350 GWp of solar PV in this mix. This is surely creating a future business prospect, considering the vast mineral content that can be repurposed at the end-of-life of solar panels. In other words, a circular economy can be built in the solar energy space, proving that waste can actually be a resource.

The Indian government has set the ambitious target of achieving 500 GW of non-fossil fuel installed capacity by 2030 as part of its net zero policy. It is expected that there will be 350 GWp of solar PV in this mix. This is surely creating a future business prospect, considering the vast mineral content that can be repurposed at the end-of-life of solar panels. In other words, a circular economy can be built in the solar energy space, proving that waste can actually be a resource.

The glass used in a typical crystalline solar PV module has antimony, and the solder paste used to interconnect the cells contains lead. The quantities of these hazardous materials are below the threshold limits for causing environmental damage. Table 1 shows the anticipated raw material requirement using crystalline solar cells under the business-as-usual scenario of 350 GWp of solar PV capacity, as per research done by Malaviya Solar Energy Consultancy. The data was arrived at with consideration of the anticipated evolution of the weight of PV modules until 2030, and market projections.

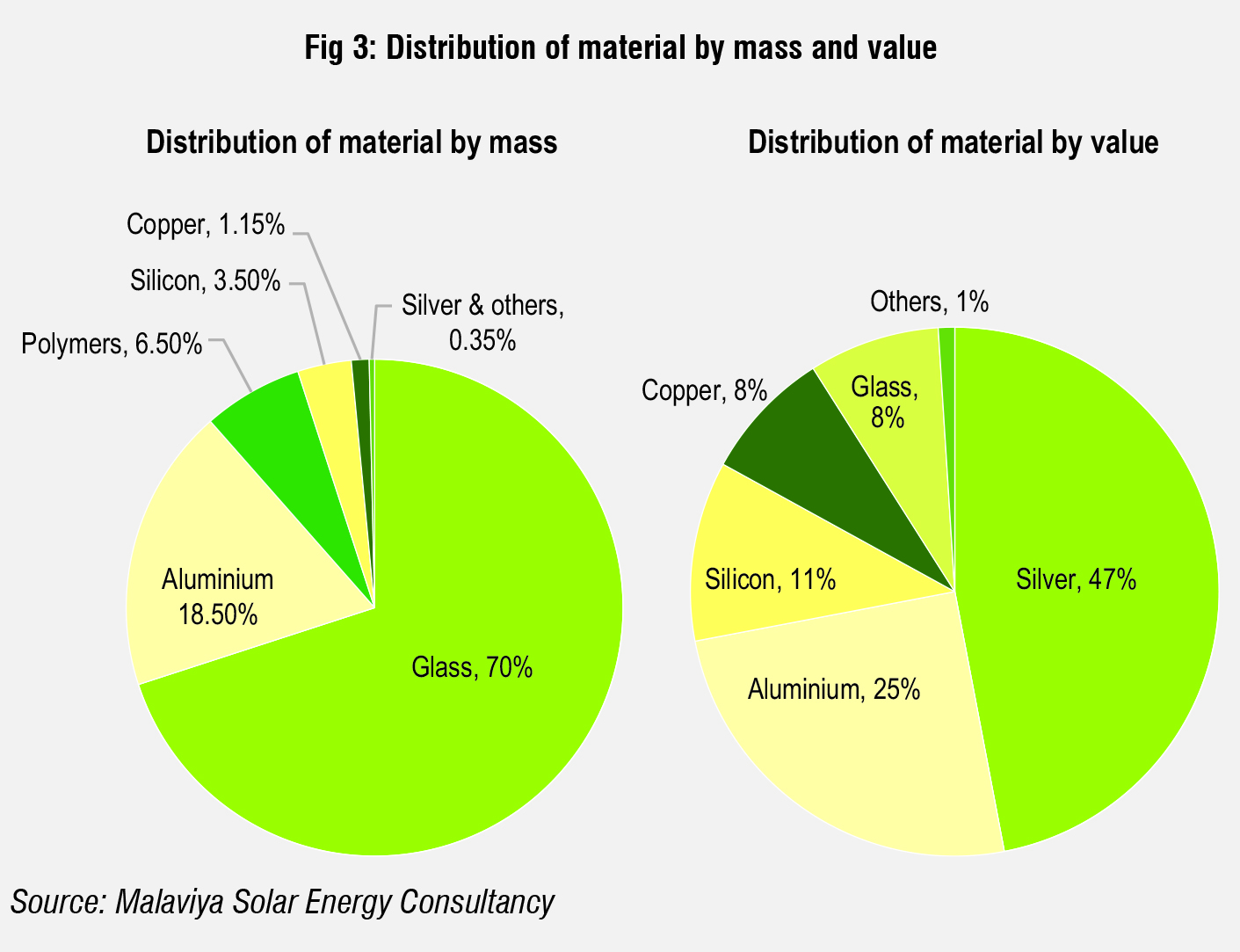

Glass is the heaviest component (70 per cent by mass), but it contributes only 8 per cent of the value of the solar PV module chain. By contrast, silver is less than 0.1 per cent by weight but valued at 47 per cent. In fact, the recovery of silver will be the driver for the recycling of solar modules. Fig 3 shows the distribution of materials by mass and value.

Glass is the heaviest component (70 per cent by mass), but it contributes only 8 per cent of the value of the solar PV module chain. By contrast, silver is less than 0.1 per cent by weight but valued at 47 per cent. In fact, the recovery of silver will be the driver for the recycling of solar modules. Fig 3 shows the distribution of materials by mass and value.

If 90 per cent of these raw materials are recycled, a little under 20 million tonnes can be repurposed for primary and secondary use. Studies have proven that using repurposed scrap aluminium and glass over virgin-grade material saves energy costs by as much as 90 per cent. This would contribute to carbon footprint reduction by reducing fresh mining.

It is equally important to note that in India, the metals used in the making of solar cells are either critical or net imported. This lends merit to recycling and becoming Atmanirbhar to fulfil requirements. While several recyclers claim to recover anywhere between 90 and 100 per cent of the metals and materials, repurposing polymers and extracting purified metals from a silicon cell still remains a challenge.

It is equally important to note that in India, the metals used in the making of solar cells are either critical or net imported. This lends merit to recycling and becoming Atmanirbhar to fulfil requirements. While several recyclers claim to recover anywhere between 90 and 100 per cent of the metals and materials, repurposing polymers and extracting purified metals from a silicon cell still remains a challenge.

It is anticipated that by 2030, India will be the second-largest global solar market after China. The states of Rajasthan, Gujarat, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Maharashtra currently have the highest potential to set up recycling facilities. With the rapid emergence of high-efficiency cells, the repowering of solar projects may become business-as-usual, meaning that PV modules will be substituted much earlier than their claimed life of 25 years (also known as Early Loss), leaving older modules to be repurposed for low-power applications or disposed of. In this scenario, the production numbers of PV modules will also rise, raising the demand for raw materials. With such ambitious targets, acquiring and disposing of raw materials will be a significant challenge.

It is anticipated that by 2030, India will be the second-largest global solar market after China. The states of Rajasthan, Gujarat, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Maharashtra currently have the highest potential to set up recycling facilities. With the rapid emergence of high-efficiency cells, the repowering of solar projects may become business-as-usual, meaning that PV modules will be substituted much earlier than their claimed life of 25 years (also known as Early Loss), leaving older modules to be repurposed for low-power applications or disposed of. In this scenario, the production numbers of PV modules will also rise, raising the demand for raw materials. With such ambitious targets, acquiring and disposing of raw materials will be a significant challenge.

Researchers in Germany have already used recycled materials to produce new solar modules. Going forward, it should stimulate a reduction in mining by upcycling scrap modules, justifying solar PV energy as a clean energy technology.

The following action points need immediate attention in order to institute circularity for solar panels and fulfil the Central Pollution Control Board’s guidelines.

- Banning the disposal of solar panels and cells in unorganised sectors

- Making solar thermal panels subject to the EPR scheme

- Strict implementation of the federal e-waste order on the safe disposal (recycling) of solar panels

- Stricter enforcement of ESG compliance by renewable manufacturers

- Incentivising producers for every EPR certificate generated

- Setting up a dedicated Ministry for Circular Economy to address climate change

- Setting up a circular economy park covering all industrial sectors – the first of its kind in India

- Floating a renewable waste policy that also includes wind turbine blades

- Extending viability gap funding for start-ups

- Ensuring over reliance on imports

- Creating a role model for circularity in renewable energy, with respect to solar panels, wind turbine blades, etc.

A collective producers’ management association can best address these issues through a single window, and fulfil the e-waste targets.

This is a silver tongue business opportunity, and global recyclers with the best technology can establish footholds in India. The massive push by the Government of India to promote private sector innovation and research with a corpus of Rs 1,000 trillion extended through interest-free loans can help establish the country as a global benchmark for solar panel circularity.